This blog is a guest post written by Daniel A. Masters. Daniel runs his own blog at https://dan-masters-civil-war.blogspot.com/?m=1

Three weeks after the Battle of Perryville, the battlegrounds were still covered with the carnage of war. “Dead horses, broken artillery wagons, haversacks, cartridge boxes, hats, shoes, remnants of clothing,” lay everywhere one Ohioan recalled. “In every field, fresh-made graves are abundant, and in places the clay soil assumes a darker hue, red with the blood of friend and foe. Since the fight, no rain has fallen, and these dark stains are still discernable.”

The most appalling scenes lie at the half-covered graves of the slain Confederates. A group of feral hogs rooted up the bodies of the dead and were tearing the limbs from them. “As we drove them away, they stood at a short distance impatiently waiting, and scarce had we turned the heads of our horses from this disgusting scene before they were again at the graves, furiously tearing limb from limb and devouring the half-corrupted flesh of those who but a few days before stood in the pride of manhood battling for home and honor,” he remembered. “Nearby these graves were the bodies of horses, yet these were scarce touched, the hogs preferring human flesh to that of animals.”

This unsigned account of the carnage of Perryville first saw publication in the November 14, 1862, edition of the Cleveland Morning Leader.

Perryville, Boyle Co., Kentucky

November 5, 1862

One of the great objects which haunted my youthful days was, when time should hang heavy on my hands and money was plenty (for like all youthful dreamers I thought manhood would bring it), I would visit some portion of the older world where grim-visaged war held reign supreme, and on the spot where contending army had met the shock of battle, view the scene where man met man in murderous strife. In these day visions I always located the battle far off, never dreaming that our own loved land would be rent with war, and American homes be bathed in blood shed in fratricidal strife.

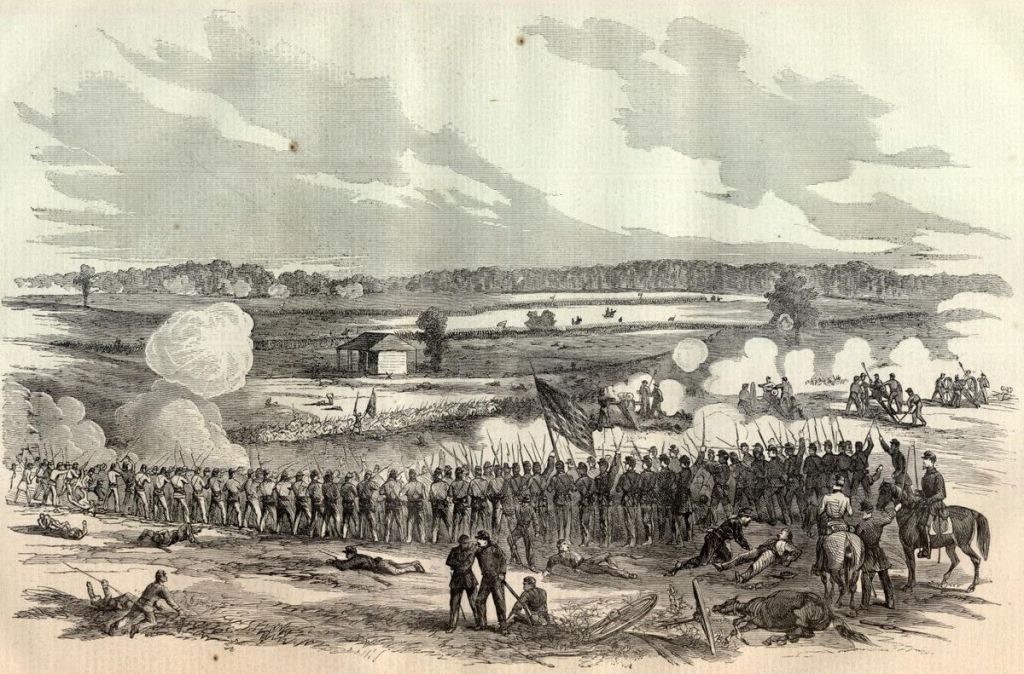

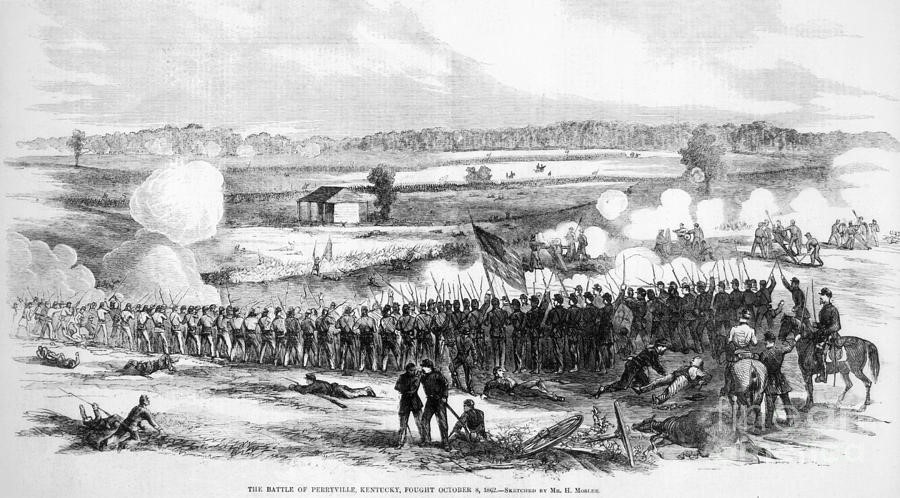

Cast by fate in this region soon after the sanguinary struggle of the 8th of October when was fought the great Battle of Chaplin Hills, my boyish dream was realized. So near to the village did the fight rage that on visiting a sick soldier a few evenings since, I was cautioned not to put my foot in an open space in the floor at the head of the stairs where a cannon ball had been and left its ugly mark. It passed through the house, tore up the floor, and passed out the opposite side. Numerous other houses were marked with cannon ball marks, and one or two persons were killed in the town.

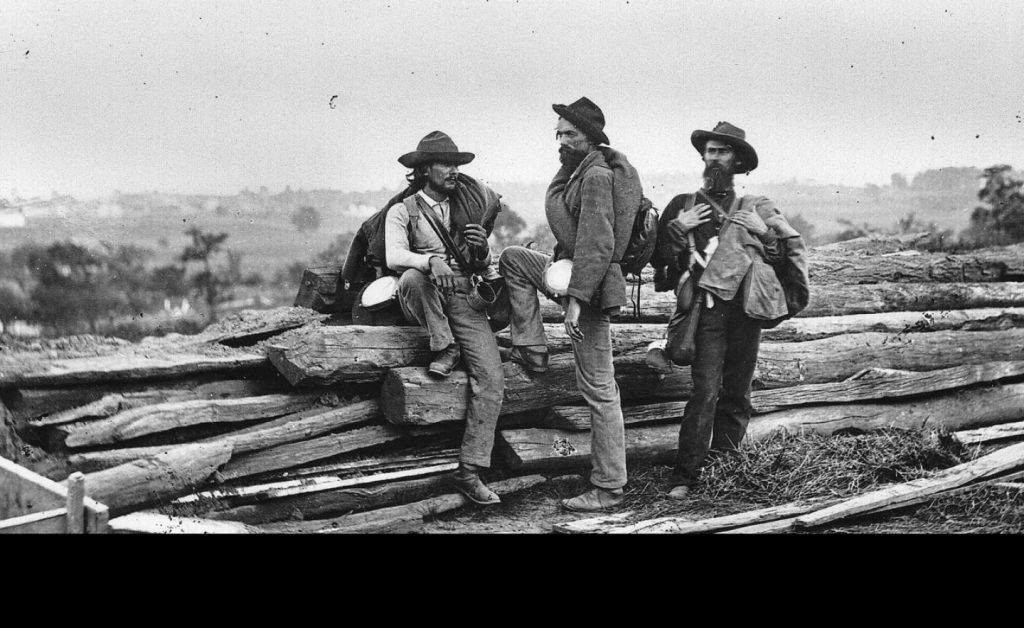

First with a soldier of the 121st Ohio mounted on the horse of Chaplain Drake, one of those rare army chaplains who not only shows the road to heaven but leads the way, I visited the battlefield to look at the carnage and then with some officers I re-visited it and had explained to me the different positions occupied by the several commands, Federal and Secesh.

The field is still covered with the debris of the fight: dead horses, broken artillery wagons, haversacks, cartridge boxes, hats, shoes, remnants of clothing, etc. In every field, and there are many for the line of battle covered miles of territory, fresh-made graves are abundant, and in places the clay soil assumes a darker hue, red with the blood of friend and foe. Since the fight, no rain has fallen, and these dark stains are still discernable.

To the honor of human nature our own dead are buried, mostly where they fell, sufficiently deep to cover them from our eye. To its dishonor the enemy are tumbled into shallow graves and in many cases parts of the blackened remains are visible above the earth. Riding by where the enemy fell in numbers, I saw a hand black with exposure, but still as delicate as that of a lady, resting on the top of the parched earth while the body to which it belonged had a thin covering of earth over it. The walnut-colored cuff of the coat still around the wrist showed that it was a secession soldier, and a physician present with us pronounced the hand that of a mere youth which had never been hardened with labor.

A few moments after, I saw another hand and part of the face protruding. In another field, an open one nearby, a swarm of long-backed and long-snouted hogs common to this part of Kentucky, had rooted into the thinly covered graves and were making their horrid banquet upon human flesh. As we drove them away, they stood at a short distance impatiently waiting, and scarce had we turned the heads of our horses from this disgusting scene before they were again at the graves, furiously tearing limb from limb and devouring the half-corrupted flesh of those who but a few days before stood in the pride of manhood battling for home and honor. Nearby these graves were the bodies of horses, yet these were scare touched, the hogs preferring human flesh to that of animals. A sight more horribly disgusting human eye never looked upon.

Occasionally we found a grave with a board at its head, giving the name, regiment, and company of the dead occupant, and these were generally protected by a rail fence or covered with stones, with which every field abounds, to protect them from the hogs who, having tasted human flesh, are more ravenous than the hyena in their taste for human gore. Around the graves thus covered, myriads of flies smaller yet resembling the green bottle-fly, swarmed on the tops of the graves and particularly the stones were black with them.

In traversing the scene of the slaughter, men, women, and children on foot and on horseback and in carriages are met, and to the honor of womanhood be it said that I saw a group of them with boards and with their own fair hands diligently engaged in scooping up the dirt to cover the exposed parts of the victims of the great slaughter laid by shallow graves and by the rooting of hogs. The woods are full of acorns, walnuts, buckeyes, and corn is scattered over the fields, and yet, fond as the hog is of these, he scarce touches them, the human banquet being chosen above all vulgar and common food. The Bible teaches us that the hog is an unclean animal, unfit for the food of man, and after the sight I saw on the field of battle, as far as pork in this region is concerned, I adopted the Jewish faith in prohibiting the eating of hogs.

A description of the battle could not, with my feeble powers, be rendered intelligible to your readers. It was terribly contested and if victory did perch on our banners, it was won at a fearful cost. The night of the battle must from all accounts have been a fearful one. Over 4,000 of the killed and wounded lay upon the field and amid the groans of the despairing wretches the continual cry for “water, water, in God’s name, give me a drop of water” was fearful and heart-rending in the extreme. With the loss of blood comes thirst, fierce and intolerable, yet blood was more plenty than water for the creek was bare of a drop and the few springs which gave forth a limited quantity were distant and difficult of access. Many a soldier that never, save at his mother’s knee, bowed his head, and lifted up his heart in supplication to his God, prayed that night for water, but none came and the parched lips received moisture alone from the life blood which trickled forth as life passes away.

Our surgeons within the Rebel lines say no discrimination was made among the suffering. Thus, Federal and Secesh received the same treatment from those having the wounded in charge, but the number was so great that bare as the Rebel army was everything but little could be done. When the Rebel army retreated, the wounded left behind received the same kind treatment from our troops and surgeons. One poor man, Surgeon Robert McMeens of Sandusky, worked to death in caring for the wounded. In the thickest and hottest of the fight, he received General James S. Jackson’s body in his arms when he fell covered with wounds, a lifeless corpse. He also bore the body of General William R. Terrill from the field and was never mentioned by the head surgeon in his report because, it is said, they were personal enemies.

Poor McMeens! He called upon me, his neckcloth covered with blood from an amputation, in the morning and talked to me half an hour about his wife whom he expected the next day to visit him. At midnight he was a corpse, dead from overwork and the deep injustice that had been done him on the official report while others less worthy were mentioned in terms of high praise. Dead though he be, the surgeons of the army will take means to vindicate his fame and his high talents, his skill as a surgeon, and above all his kind and gentle heart, his gallant and noble bearing; these will long live in the breasts of those who knew him best and loved him most.

Source:

Letter from unknown correspondent, Cleveland Morning Leader (Ohio), November 14, 1862, pg. 2

Leave a Reply