Introduction

The Battle of Gettysburg, fought from July 1 to July 3, 1863, remains one of the most pivotal engagements of the American Civil War. It is often remembered for its scale, the staggering number of casualties, and its pivotal role as a turning point in the conflict. Yet the battle’s outcome was shaped decisively by the events of its opening day. On July 1 (Battle at Gettysburg day 1), Union and Confederate forces converged unexpectedly on the small Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. What began as a skirmish between cavalry and infantry escalated into a full-scale clash involving tens of thousands of soldiers. The first day ended with Union forces retreating through the town, battered but not broken, and rallying on the commanding high ground south of Gettysburg. This essay examines the first day in detail, tracing its phases, analyzing leadership decisions, and considering its strategic consequences.

Strategic Context – Civil War

In the early summer of 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee launched his second invasion of the North, beginning the Gettysburg campaign. Following his victory at Chancellorsville, Lee sought to relieve pressure on war-torn Virginia by securing supplies from Pennsylvania’s fertile countryside. He hoped this would deliver a blow that might encourage foreign recognition of the Confederacy or weaken Northern morale. His Army of Northern Virginia, numbering around 75,000 men, advanced into Pennsylvania. Opposing him was the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Major General George G. Meade, who had assumed command only days before the battle. Meade’s army, roughly equal in size, shadowed Lee’s movements, seeking to protect Washington and Baltimore while awaiting an opportunity to strike.

Gettysburg was not chosen deliberately as the site of battle. Rather, its road network made it a natural point of convergence. Confederate forces under Lieutenant General A.P. Hill and Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell approached from the west and north, while Union cavalry under Brigadier General John Buford had already occupied the town. The stage was set for an encounter neither side had fully anticipated.

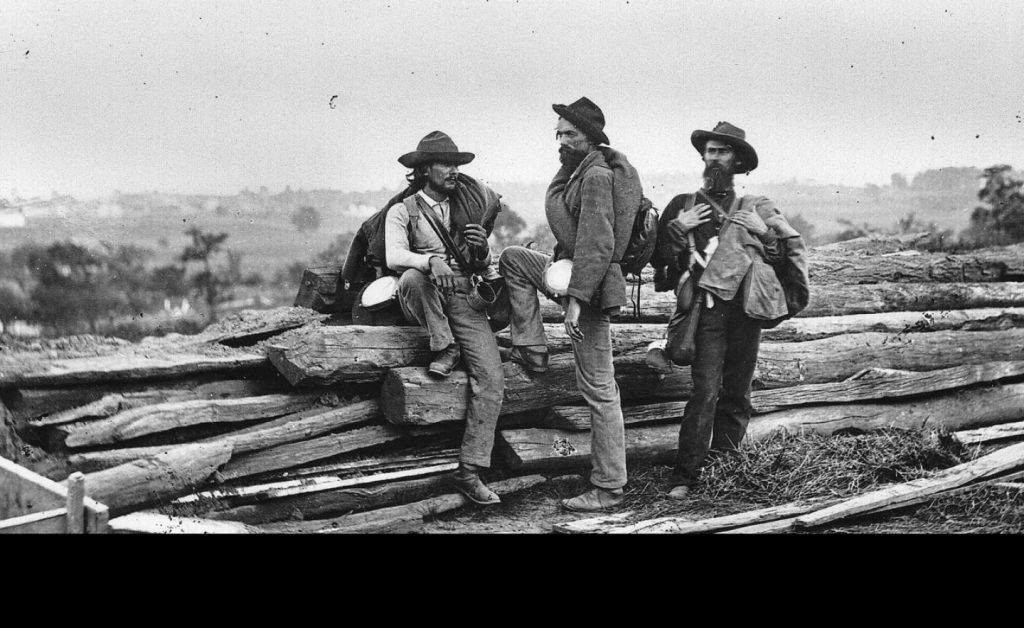

Phase One: Buford’s Defense on the Battlefield

At dawn on July 1st, Major General Henry Heth’s division of Hill’s corps advanced eastward along the Chambersburg Pike toward Gettysburg. Expecting only militia or light resistance, Heth’s men instead encountered Buford’s cavalry, who fired the first shot. General Buford, a seasoned officer, recognized the tactical importance of the ridges west of Gettysburg—Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge, and Seminary Ridge. He dismounted his cavalry and deployed them as infantry, using their carbines to delay the Confederate advance. His goal was not to defeat Heth but to hold long enough for Union infantry to arrive.

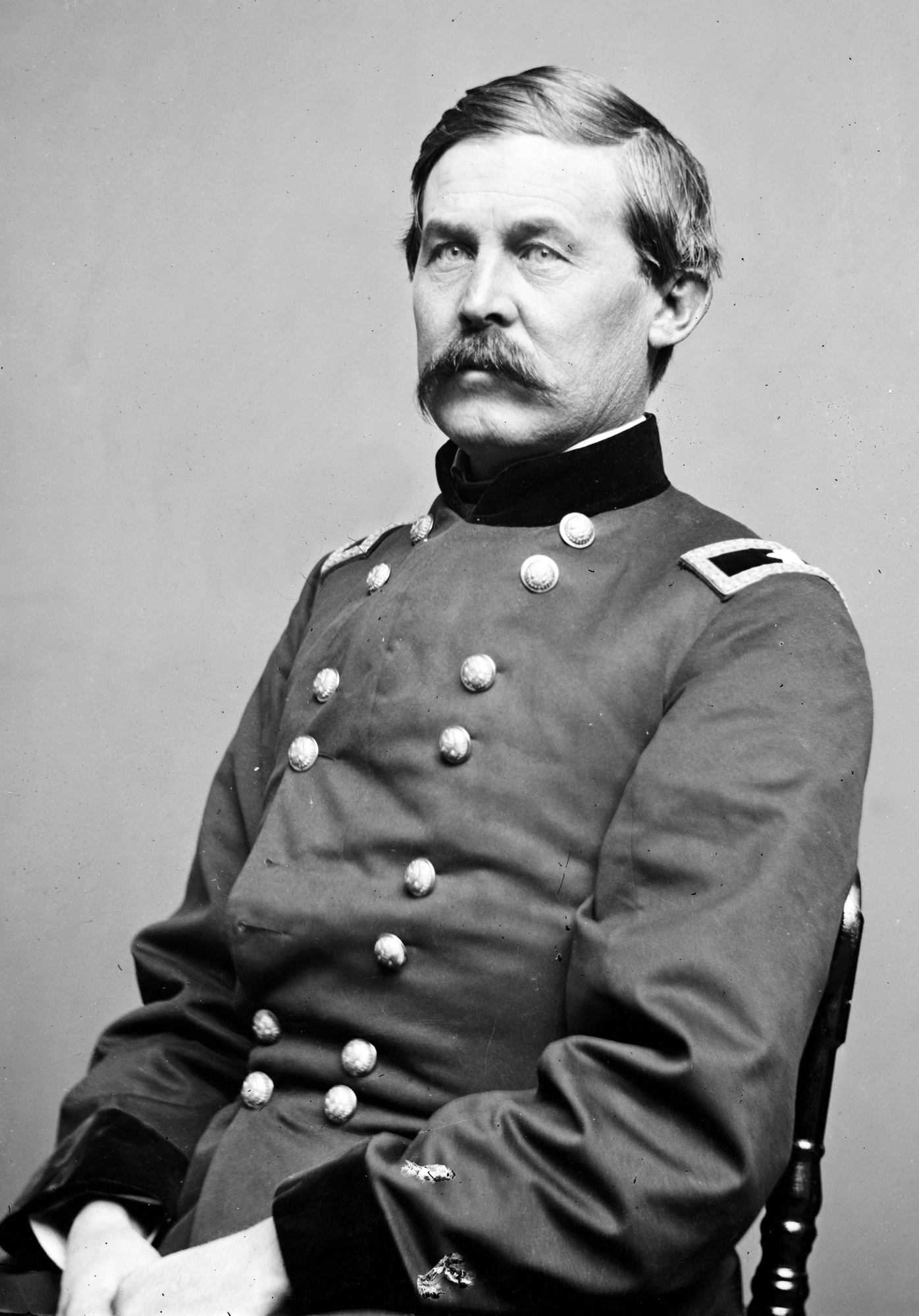

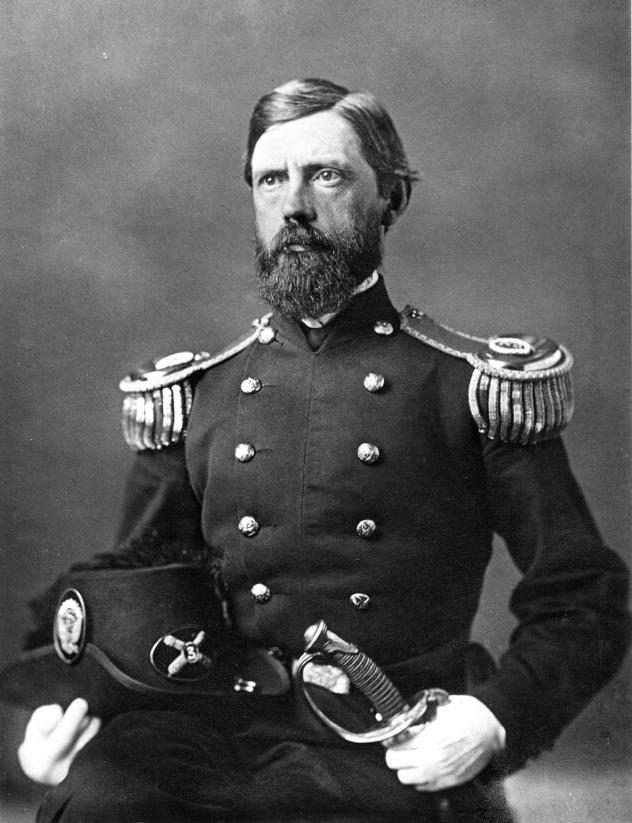

Buford’s defense was masterful. His troopers fought stubbornly from cover, slowing Heth’s brigades and inflicting casualties. By mid-morning, Union reinforcements arrived: the I Corps under Major General John Reynolds. Reynolds, one of the Union’s most respected commanders, immediately committed his men to the fight. Tragically, Reynolds was killed early in the action, struck by a bullet while directing troops near McPherson’s Ridge. His death deprived the Federal troops of a capable leader, but his decision to engage ensured that the Union army would contest the ground vigorously.

Phase Two: Escalation of Combat

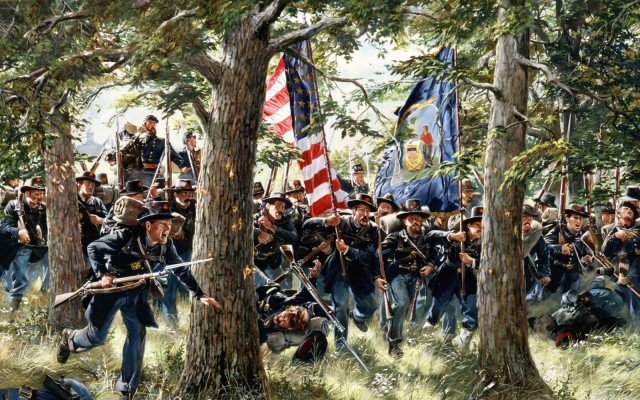

With Reynolds fallen, command of I Corps passed to Major General Abner Doubleday. The Union infantry fought fiercely against Heth’s division, repelling repeated assaults against the Union line. The terrain favored the defenders: fences, ridges, and woodlots provided cover, while Union artillery supported the infantry. By late morning, however, Confederate reinforcements under Major General Dorsey Pender arrived, adding weight to the attack.

The fighting around McPherson’s Ridge was intense. Union brigades under commanders such as Brigadier General James Wadsworth resisted valiantly, but the pressure mounted. Meanwhile, to the north of town, Ewell’s corps approached. Around midday, Ewell’s divisions engaged Union XI Corps under Major General Oliver O. Howard. Unlike the strong positions west of town, the ground north of Gettysburg was open and vulnerable. Howard’s troops, many of them German immigrants, faced overwhelming assaults from Confederate divisions under Generals Jubal Early and Robert Rodes.

Phase Three: Union Collapse and Retreat

By mid-afternoon, the Union position became untenable on the Gettysburg battlefield. The I Corps, exhausted and outnumbered, began to fall back. The XI Corps, pressed hard from the north, collapsed in disorder. Confederate forces surged forward, driving Union soldiers through the streets of Gettysburg. Thousands were captured in the chaotic retreat. Yet the Union army did not disintegrate entirely. Howard had earlier identified the high ground south of town as a strong defensive position. He directed retreating units to rally there.

This retreat, though costly, proved decisive. By evening, Union forces had established a defensive line on terrain that dominated the surrounding area. Confederate forces, victorious on the field, failed to press their advantage. General Ewell, ordered to seize Cemetery Hill “if practicable,” hesitated. Fatigued troops, uncertainty about Union strength, and ambiguous orders led him to delay. As a result, the Union army held the high ground, setting the stage for the next two days of battle.

Leadership and Decision-Making

The first day at Gettysburg highlights the importance of leadership decisions. Buford’s foresight in occupying the ridges west of town delayed the Confederate advance and ensured Union infantry could arrive. Reynolds’s prompt commitment of I Corps, though costing him his life, stabilized the situation at a critical moment. Howard’s recognition of Cemetery Hill as a rallying point preserved the Union army from destruction.

On the Confederate side, Heth’s decision to advance without adequate reconnaissance exposed his division to unexpected resistance. Lee’s orders to Ewell, couched in conditional language, contributed to hesitation at a decisive moment. Had Ewell seized Cemetery Hill on July 1, the Union army might have been denied its strong defensive position, altering the course of the battle.

Casualties and Human Cost of the Battle

The first day of Gettysburg was bloody. Union casualties numbered around 9,000, while Confederate losses were approximately 6,000. Among the fallen was General Reynolds, whose death symbolized the day’s toll on leadership. Civilians in Gettysburg witnessed the chaos firsthand, as fighting raged through fields and streets. The town itself became a battleground, with homes and churches pressed into service as hospitals. The human cost underscored the ferocity of the engagement and foreshadowed the even greater carnage to come.

Strategic Consequences of the First Day of the Battle of Gettysburg

Tactically, July 1 was a Confederate victory. Lee’s forces had driven the Union army through Gettysburg and inflicted heavy casualties. Yet strategically, the outcome favored the Union. By rallying on Cemetery Hill and adjacent ridges, the Union army secured terrain that would prove nearly impregnable. Lee’s failure to seize this ground on July 1 forced him into costly frontal assaults on July 2 and 3. The Union’s defensive position, anchored on high ground and interior lines, enabled Meade to repel Confederate attacks and ultimately secure victory.

Thus, the first day at Gettysburg illustrates the paradox of tactical success and strategic failure. The Confederates won the field but lost the opportunity. The Union lost ground but gained a position that would decide the battle.

Conclusion and Consequences (Gettysburg Address)

The first day of the Battle of Gettysburg saw intense clashes, strategic maneuvers, and pivotal decisions that would shape the course of the conflict. From General Buford’s valiant defense on McPherson’s Ridge to the Union’s strategic retreat through the town, the day showcased the determination of soldiers and the importance of the geographical landscape. While the Confederates gained early victories, their failure to secure Cemetery Hill allowed the Union forces to establish a fortified position that ultimately proved crucial in their ultimate success. The Battle of Gettysburg culminated in Pickett’s charge and the Confederate defeat, with Abraham Lincoln arriving in November to deliver the Gettysburg Address.

Looking back, July 1 served as a precursor to Union victory, emphasizing the critical role that planning, leadership, and unforeseen circumstances play in the outcome of battle.

Leave a Reply