Perryville was a crucial battle of the Western Theater fought on October 8, 1862. The consequences of the battle significantly impacted the trajectory of the war. Civil War enthusiasts who eschew in-depth reading of battles that don’t include the “big names” frequently overlook it. Nevertheless, critical events determined the war’s outcome despite an undistinguished cast of characters. Perryville featured Confederate armies under Generals Edmund Kirby Smith and Braxton Bragg versus a larger Union force under General Don Carlos Buell.

General Don Carlos Buell

Kentucky – Crucial Border State

Kentucky was a border state that tried to remain officially neutral after the Civil War started but ended up divided, with General Grant at Paducah and General Polk in Columbus. After Shiloh, General Halleck besieged Corinth with a combined force of over 100,000 men, including the armies Grant, Buell, and Pope commanded. Beauregard at Corinth had less than half that number. When he abandoned that crossroads town, Davis replaced him with General Braxton Bragg, who moved to Tupelo, MS. Meanwhile, Halleck was summoned to DC to become commander-in-chief and Pope to run the eastern theater. Buell moved towards Chattanooga while Grant began wrestling with the problem of Vicksburg.

Braxton Bragg

Bragg realized that controlling Kentucky was crucial to the defense of the Western theater. It was the underlying idea advanced by Kirby Smith, who believed that an offensive action could have important consequences on the war. Kentucky was an important military target because Smith thought it would alleviate the supply problems and divert the Union armies from their movements. An invasion of Kentucky would also threaten Indiana and western Ohio. The idea was to make the Ohio River the Confederates’ northern border. Their plan was an invasion of the North, and it was the first of the war, preceding Lee’s crossing over to Maryland in the Antietam campaign.

Bragg moved his 30,000 men to Chattanooga to join Smith. They met on July 31 and decided to split the army. Two of Bragg’s brigades would join Smith to march into Kentucky with the idea that if Buell went after Smith, Bragg would march north against his rear. He also sent his cavalry under John Hunt Morgan north into Ohio. The plan was to force their way through the Federal screen at the northern Tennessee border during the second half of August.Grant was expected to remain where he was pursuing Vicksburg. When the armies combined, Bragg would be the more senior commander. Smith wasn’t pleased with this arrangement, and it would prove to be a critical determinant of the campaign.

The Campaign

The Confederate plan to invade Kentucky was bold but risky. To succeed would require perfect coordination between two separate armies with no unity of command. On reflection, Bragg had second thoughts but proceeded under pressure from President Davis. But Smith abandoned the agreement, anticipating that a solo victory would bring him personal glory. He deceived Bragg as to his intentions, requesting two additional brigades, supposedly for the expedition to Cumberland Gap. On August 9, Smith informed Bragg that he was breaking the agreement and intended to bypass Cumberland Gap, leaving a small holding force to neutralize the Union garrison and move north. Unable to command Smith to honor their plan, Bragg focused on a movement to Lexington instead of Nashville. He cautioned Smith that Buell could pursue and defeat his smaller army before Bragg’s army could combine forces.

Colonel Phil Sheridan discovered that Bragg was no longer in Tupelo and was on the move. He was subsequently promoted to Brig Gen as a result of this reconnaissance. Buell abandoned his slow advance toward Chattanooga upon recognition of these movements, Instead, he concentrated his army at Nashville to place his army between the Confederates and Louisville and Cincinnati. When the Confederate forces initiated the invasion of Kentucky Buell abandoned his campaign in Tennessee. At the end of August 1862, Bragg moved to recapture Kentucky.

The Battle of Richmond, on August 29-30, resulted from these movements. The battle was a series of crushing frontal assaults led by rising star general Patrick Cleburne, followed by a well-timed cavalry pursuit. The better-positioned and better-led Confederate troops annihilated the Provisional Army of Kentucky in perhaps the most complete Southern victory of the entire war.

One consequence of the battle was that Buell, at Nashville, now became aware of the Confederate threat. By September 7th his men had abandoned their offensive positions and were beginning a 200-mile withdrawal to establish a new line around the Kentucky capital of Louisville. In Louisville, Buell reinforced his army and then dispatched 20,000 men under Brig. Gen. Joshua W. Sill toward Frankfort. His plan was to prevent the two Confederate armies from joining forces.

On September 17, at the Battle of Munfordville (September 14-17, 1862), Bragg captured an important rail station and 4,000 Union soldiers. Buell was in a tough position: Bragg’s army was located between Buell and the Union supply center at Louisville, Kentucky. Buell withdrew around Bragg’s army to Louisville.

https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/don-carlos-buell

Bragg then had to decide whether to continue toward Louisville and a battle with Buell or to rejoin Smith, who had captured Richmond and Lexington, threatening Cincinnati. Bragg chose the latter to maintain an offensive posture. Bragg met Smith in Frankfort to make plans for the upcoming operation.

Despite these small-scale Confederate victories, two major problems were evident: First, they were disappointed in how many recruits they were attracting in Kentucky. They had expected around 30,000 less than 3000 had joined. Buell’s Army of the Ohio was composed of 55,000 men, outnumbering the two southern armies by more than two-to-one. Moreover, Kentuckians were joining Buell at Louisville.

Even worse water was scarce. The drought in central and northern Kentucky caused hundreds of deaths in both armies. In the autumn of 1862, the upper south west of the Appalachians and Midwest were locked in the worst drought in memory. So severe was the drought that when they arrived in Louisville, some of Buell’s Hoosiers just kept walking, across the Ohio River toward home. Indeed both armies had marched north into Kentucky absolutely desperate for water, and as a result the men were both dehydrated and sick due to the microbes they had ingested by drinking anything wet. Good water was a prize. On October 7, when Bragg directed Polk to stop at eliminate the pursuing Federal threat, he reunited his force in Perryville, taking tactical advantage of the hills west of town but also guarding a series of springs as well as the puddles in the bed of the Chaplin River.” Ken Noe https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/battle-perryville-then-now

On October 4th, Bragg entered Perryville, a small town 75 miles southeast of Louisville whose sole importance was a network of waterways nearby. Both sides tried to gain control of the area’s water: the strategic basis of this battle was over water supplies. Buell went in pursuit of Bragg knowing that the other half of the army under Kirby Smith was distant. He took his much larger army and approached the crossroads town of Perryville, Kentucky where Bragg was camped.

The Battle Begins

After moving into Louisville unopposed, Buell’s forces met Bragg’s army at the Battle of Perryville, or the Battle of Chaplin Hills, on October 8, 1862. The two armies encountered each other northwest of Perryville shortly after midnight on October 8th. Buell’s men were scattered because over two-thirds of his army had delayed their march to search for water away from the approach road. Bragg’s army was united but was outnumbered even in front of this fraction of Buell’s force.

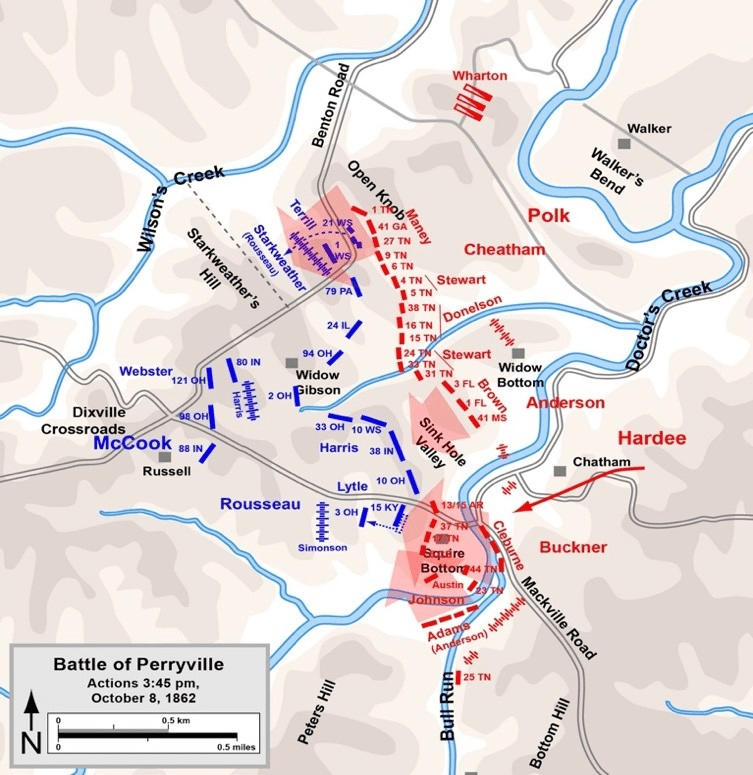

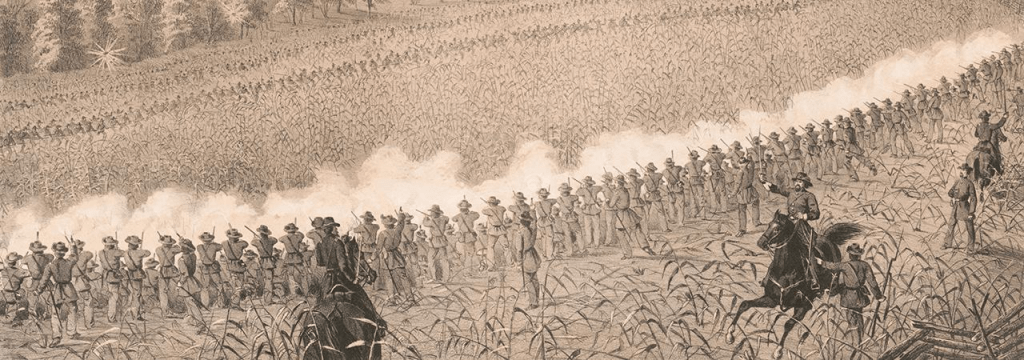

The rolling Chaplin Hills almost immediately rise west of town was the key topographical feature. Those hills provided excellent high ground for an army on the defensive. On the other hand, they could completely screen Bragg’s assault columns until the very last minute. The history of the battle is full of accounts of the enemy suddenly appearing at close range, seemingly out of nowhere, as well as the shock, confusion, and hard fighting that followed. Ultimately, the Confederate attack required men to fight uphill all afternoon, over one ridge and then another, no easy task in hot and dry weather, while the Federal defenders effectively use the same hills to their best advantage.

Bragg didn’t have a formal battle plan; it was all improvised on the spur of the moment. Bragg was convinced that most of Buell’s army was miles to the north, about to overwhelm Kirby Smith’s army. His original plan was to consolidate the two Confederate armies before fighting, but on October 7 he hastily ordered Leonidas Polk to halt his march, turn, and quickly destroy the Federal force that had approached from Louisville before resuming the march north. Polk and William J. Hardee believed they faced a division or two. Facing a more sizable and aggressive force than expected, Polk instead fell back on the morning of October 8 into a poorly designed defensive line west of town and fought off the Union III Corps through the morning.

The battle was fought on this ground because Bragg was convinced that most of Buell’s army was approaching Frankfort and Lexington while a small contingent threatened the Confederates camped to the south at Bardstown. In fact, the opposite was true. Bragg ordered Leonidas Polk to bring the army north. Passing through Perryville the first time, few soldiers took note of it, but Bragg’s engineers had already marked it for two reasons. First, the town served as the hub of the regional road network that connected Bardstown with Danville, Harrodsburg, and ultimately Lexington. Although Bragg didn’t realize it, those roads were funneling Buell’s temporarily divided army straight into Perryville.

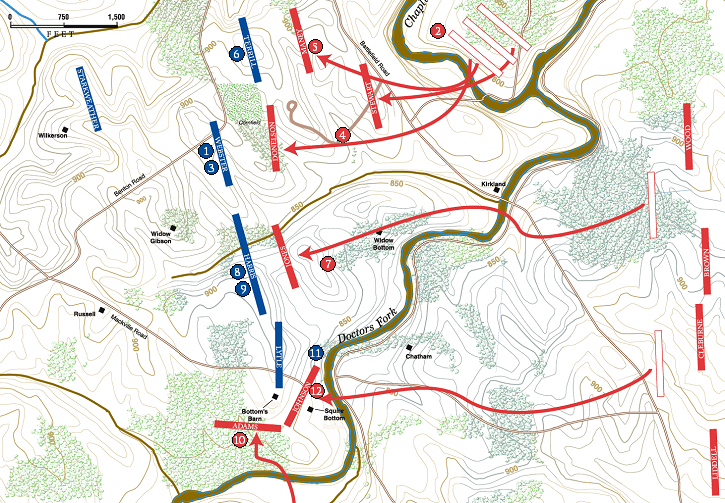

When he arrived in Perryville at about 10:30 AM furious Bragg demanded an attack, still unaware that Buell’s entire army was arriving in Perryville. Discovering the flaws in Polk’s deployments, and notably a right flank in the air, he shifted troops north for an anticipated flanking assault en echelon. As more and more Federal troops arrived on their left, however, Polk continued to delay while shifting his men farther and farther north. The attack finally began at 2 P. M., with Benjamin Franklin Cheatham’s division attempting to seize the presumably open Union left while the rest of the Confederate army assaulted the Union line, rolling north to south.

The Battle of Perryville

Assuming that the Confederates would settle into a defensive stance, Buell resolved to wait until his army came together before launching the decisive attack. In the meantime, his soldiers nearest Perryville tested the Southern picket line around Doctor’s Fork. Sharp skirmishing erupted before daybreak as small detachments struggled bitterly for access to the dirty water.

Thinking that this fighting indicated the furthest northern end of Buell’s battle line, the Confederates deployed their brigades to strike the Union forces from the front and northern flank. Bragg had no intention of waiting another day for Buell to attack. Instead, Bragg ordered a division to attack the Union left flank. The full force of Buell’s command was gathering when Bragg attacked. Buell was 2 miles behind the frontline and was unaware that he was under attack. More troops were sent by Bragg but not by Buell, resulting in a Union retreat until finally reinforced. Then, Bragg, recognizing that he was outnumbered and short of supplies, withdrew.

Buell didn’t realize he was under attack and thought he was planning an attack for October 9th. He reportedly was recovering from a fall from his horse caused by an angry forager who grabbed the general’s mount’s bridle when Buell confronted him. He might have acted differently had he heard the afternoon fighting, but the atmospheric phenomenon known as “acoustic shadow” masked the sound of small arms fire at headquarters. Since he could not hear the battle, when aides and subordinates tardily began arriving and describing a major Confederate onslaught, Buell did not fully believe them. In the end, he shifted barely enough units to stem the final Confederate assault, while continuing his planning for a battle the next day.

The battle went well for the Confederates initially. Facing stubborn resistance, the Rebels gradually drove the Federals back nearly one mile. Only one corps of the Union army participated in the fighting, significantly weakening Buell’s ability to destroy Bragg’s forces. A mile away when the battle began, Buell was initially unaware of the engagement, perhaps due to an acoustic shadow. As the day progressed, however, more of Buell’s army arrived on the scene.

Both commanding officers misunderstood what was happening, and their subordinates added to the confusion with orders and countermanding commands, cavalry was misused, and so the rank-and-file was left to slog it out in a series of desperate charges and defenses over broken and deceiving ground. Indeed the Chaplin Hills so effectively masked both batteries and approaching troops that much of the fighting took place at unusually close range. Friendly fire was common. On Starkweather’s Ridge, men fought with bayonets and clubbed muskets, and slipped and fell in the blood. Then factor in the time factor. The battle began at two in the afternoon, which meant that the Confederates were desperate to achieve a breakthrough before dark even as Union soldiers hoped to just hang on until night. That desperation added to the intensity. The result was a battle that many Shiloh veterans described as the more severe. Indeed, Sam Watkins famously declared it the most severe battle of the war that he experienced.

Aftermath

As a result, Buell failed to engage his entire army, and the next day he did not heed his subordinates’ advice to counterattack because he did not know the size of the forces he faced. He outnumbered them 60,000 to 16,000.

Running short of supplies and ammunition and faced with the prospect of squaring off with the bulk of Buell’s army on the following day, Bragg withdrew during the night, despite suffering fewer casualties and scoring a tactical victory at Perryville.. He had pushed his opponent back for over a mile. But his precarious strategic situation was clear, and he retreated. Kentucky remained in Union control for the rest of the war. This is considered one of the turning points of the war and thus a strategic Confederate defeat.

Of the 55,396 Union and 16,800 Confederate troops in the area, just 20,000 Union troops and 16,800 Confederate troops participated, which is rather a small battle considering its importance. Union casualties totaled 4,276 (894 killed, 2,911 wounded, 471 captured or missing). Confederate casualties were 3,401 (532 killed, 2,641 wounded, 228 captured or missing). By percentage, the difference is not large. But the 20% casualty rate overall shows that this was one of the most desperate fights of the war. Although Union losses were higher, Bragg withdrew from Kentucky when the fighting was over, and therefore Perryville is considered a strategic victory for the Union.

Buell did not pursue the retreating Confederates, claiming that he lacked essential supplies. On October 24, 1862, President Lincoln relieved Buell from his command because of his inaction. Buell was subsequently relieved of all field command. Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans was appointed to command the Army of Ohio. He was also appointed to the command of the Department of the Cumberland and subsequently renamed his forces the Army of the Cumberland. On 25 March 1863, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside assumed command of the Department of the Ohio headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio – the second Army of the Ohio.

Bragg’s inability to control Kirby Smith—a situation created both by Richmond’s departmental system and Jefferson Davis’s fondness for Kirby Smith—seriously undermined the Confederate effort in Kentucky. I went into this project admiring Kirby Smith and frankly came out all but loathing the man. His chief goals were to maintain independent command while becoming the heroic liberator of Kentucky, going so far as to refer to himself as “Moses.” Accordingly, he made agreements with Bragg only to break them, undermined Bragg in letters to Davis, exaggerated Federal strength at Cumberland Gap to justify his independent march into Kentucky, and went in the opposite direction when Bragg asked him to move toward his army once he entered Kentucky, and ducked Bragg’s requests for supplies. And there was nothing Bragg could do about it until the two armies united. Ultimately, Kirby Smith was not at Perryville when Bragg needed him, and that sealed the failure of the campaign.” Ken Noe. See: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/battle-perryville-then-now

Perryville occurred just three weeks after Antietam and President Lincoln’s issuance of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation stole the headlines. Soon those headlines turned to the November Union elections as well as other battles in Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. Then, the Western theater wasn’t considered that important. Ken Noe suggests that the acoustic shadow continued well after the battle. Buell vs Bragg with just 1400 dead combined barely ranks it as a “major” battle, but it was. Some historians have considered Perryville the “High Water Mark” in the Western theater because it was the most northerly battle there.

After the Battle of Perryville, Bragg retreated to Harrodsburg, Kentucky, where he joined forces with Lieutenant General Kirby Smith. The combined Confederate army was now comparable in size to Buell’s army. Nevertheless, Bragg lost his enthusiasm for the campaign. Over the objections of Smith and his subordinates, Bragg called off the offensive and evacuated Kentucky. Bragg’s forces held the field, though, and continued to control the area until forced to withdraw three months later following the Battle of Stones River. This, while the battle is sometimes considered a tactical Confederate victory, it was certainly a strategic defeat.

The End of Buell’s Career

After the Battle of Perryville, Buell clashed with the Union high command over tactics and neglected to adequately pursue Bragg’s retreating Confederates. As a result, he was removed from command of the Army of the Ohio on October 24, 1862, and replaced by General William S. Rosecrans. A military commission subsequently investigated Buell’s actions, and he went over a year without orders. The commission met from November 24, 1862, to May 10, 1863, but it never issued a final report. From May 10, 1863, through June 1, 1864, Buell’s official status was “awaiting orders.”

Although several commanders—including both Grant and Sherman—would later request his services, Buell was not restored to command. Buell was finally removed from volunteer service in May 1864 and then resigned from his regular army commission shortly thereafter. From Grant’s Memoirs: “General Buell was a brave, intelligent officer, with as much professional pride and ambition of a commendable sort as I ever knew. … [He] became an object of harsh criticism later, some going so far as to challenge his loyalty. No one who knew him ever believed him capable of a dishonorable act, and nothing could be more dishonorable than to accept a high rank and command in war and then betray the trust. When I came into command of the army in 1864, I requested the Secretary of War to restore General Buell to duty.”

Army officials offered Buell new battlefield commands, but he refused to serve under officers that he once outranked. With his military reputation irreparably damaged, Buell mustered out of volunteer service on May 23, 1864, and he resigned from the military on June 1.

In 1864, Buell supported George McClellan’s Democratic Party bid for the Presidency and openly attacked the Union leadership for how it was waging the war. He moved to Kentucky at the end of the Civil War and ran a successful mining company for several years. He later worked as a pension agent from 1885 to 1889. Buell died in 1898 at the age of 80.

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/don-carlos-buell

Leave a Reply