One of my all-time favorite movies is Ron Maxwell’s 1993 epic Gettysburg, a historical masterpiece that focuses on the events of the Battle of Gettysburg from the perspectives of four of its key players on opposing sides: Robert E. Lee, James Longstreet, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, and John Buford. Filmed on location at Gettysburg National Military Park and Adams County, Pennsylvania, this production captures the engagement with spot-on historical accuracy and features stellar performances from the cast, together with a powerful musical score. The film presents a balanced portrayal of both sides, commemorating the heroism and sacrifice of Union and Confederate soldiers at pivotal moments of the battle, such as Chamberlain’s defense of Little Round Top and Pickett’s Charge. Viewing Gettysburg at a young age inspired my passionate interest in Civil War history, which I have actively pursued in my collegiate career. However, now that the thirtieth anniversary of the film’s release has passed, there are various aspects of the Gettysburg Campaign and the battle itself which are omitted from Maxwell’s depiction of the campaign and battle, and for scholars of Civil War history, studying the cinematic portrayal with the advantage of historical study can yield important insights for contemporary viewers, particularly considering the current debate over Civil War monuments and narratives.

The film opens by introducing Henry Thomas Harrison (Cooper Huckabee), a Confederate spy on a mission to monitor the movements of the Union Army of the Potomac as Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia advances through Pennsylvania during its second invasion of the North. Upon discovering that the Army of the Potomac, approximately 80,000 strong, is on the move in pursuit of the Confederates, he reports his findings to James Longstreet (Tom Berenger), Lee’s trusted subordinate and commander of the First Corps. While initially skeptical of Harrison’s report, Longstreet presents his information to General Lee (Martin Sheen), who is wary of the uncorroborated news due to the absence of J.E.B. Stuart (Joseph Fuqua), the renowned cavalry commander whom Lee considered the “eyes and ears” of the ANV. Nonetheless, with Longstreet’s assurance that they have no choice but to trust Harrison’s information, Lee decides to concentrate the widely spread out ANV in the vicinity of Gettysburg, a central location where all the roads converge. Historically, this was a critical development for the progress of the invasion since the three corps of the ANV were advancing in different areas of southwestern Pennsylvania, with Lee having ordered Richard Ewell’s corps to seize the state capital of Harrisburg if possible. Harrison’s report, however, prompted Lee to concentrate his army to meet the advancing Army of the Potomac, setting the stage for the collision of the two armies at Gettysburg.

The film then introduces Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (Jeff Daniels), the former Bowdoin College professor now serving as colonel of the 20th Maine Infantry, who is tasked with mustering 120 mutineers from the disbanded 2nd Maine Infantry into his regiment, with the provision to execute any men who refuse to follow orders. However, after listening to the grievances of the mutineers, he relies on his expertise in rhetoric, rather than force, to persuade them to take up arms again for the Union. In an impassioned speech, Chamberlain elaborates upon how this war differs from previous conflicts since the Union army is “an army out to set other men free,” declaring that human dignity, being judged by one’s actions, and “the idea that we all have value” are the essence of the Union cause. In many ways, Chamberlain’s speech epitomizes a combination of ideals that motivated Union soldiers during the Civil War, regardless of their personal feelings about slavery and race. While scholarly study of period correspondence has indicated the desire to preserve the Union as a primary motivation for most Union soldiers, a small minority were driven by hatred of slavery. Moreover, a wide cross-section of Union soldiers, though not necessarily sympathetic to enslaved African Americans, viewed their cause through the lens of preserving the nation’s democratic ideals of individual merit and civic equality from what they considered an aristocratic Southern conspiracy to destroy the American republic, which Abraham Lincoln called “the last best hope of earth.” Considering this, Chamberlain’s speech, while serving a dramatic purpose in the film, is historically significant since it appeals to the various ideological convictions that Union soldiers fought for, irrespective of their personal views on slavery.

The issue of slavery plays a central part in Chamberlain’s motivation for fighting, which he later discusses with his close confidante Buster Kilrain (Kevin Conway) after encountering an escaped slave discovered by Union soldiers. Similarly, the role of slavery as a central factor in the war is raised by James Longstreet in his conversation with British observer Arthur Fremantle (James Lancaster) about the prospects of a British alliance with the Confederacy: When Fremantle expresses his hope that such an alliance will take place, Longstreet replies, “Your government would never ally itself with the Confederacy that had the institution of slavery. You know that, and so do I. We should have freed the slaves, *then* fired on Fort Sumter.” Historically, while Longstreet aligned himself with the Republican Party and endorsed civil rights for African Americans in the postwar years, there is no known record of his expressing antislavery sentiments during the war. In addition, from the lens of contemporary Civil War scholars, Longstreet’s statement would not make any logical sense since abolishing slavery in 1861 would have removed the Confederacy’s principal reason for coming into existence, given that the fear of emancipation was expressly cited in Southern states’ ordinances of secession and the speeches of Southern leaders. It was for this same reason that many Confederate congressmen vehemently opposed the call for enlistment of black troops, with the promise of freedom for their service, as the Confederacy suffered ever-increasing manpower shortages in the final years of the war.

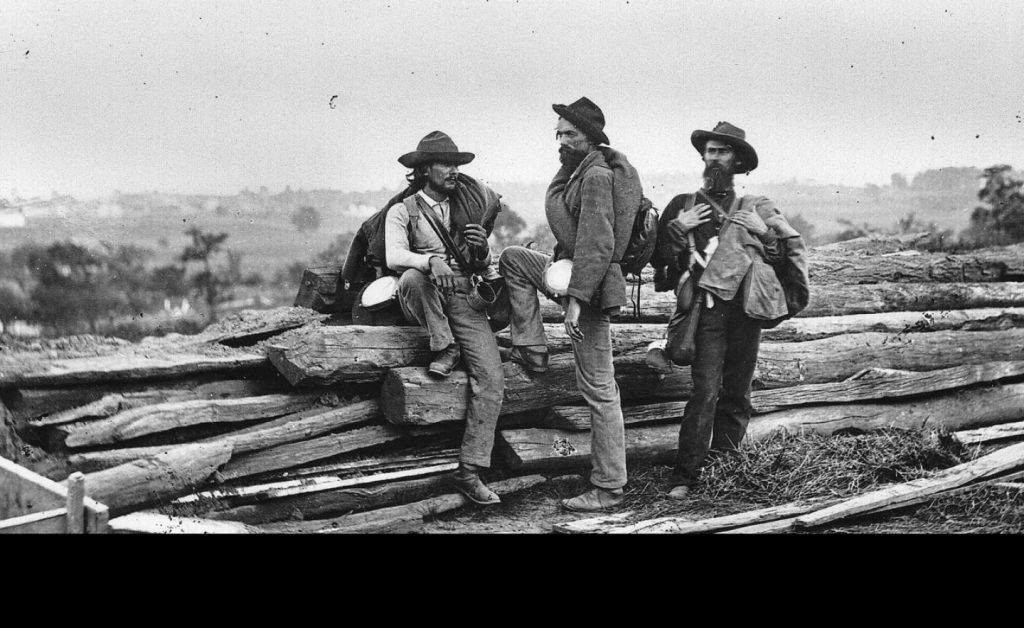

While the issue of slavery is acknowledged in Maxwell’s film, a key omission that he makes in his depiction is the way in which it influenced the conduct of the Army of Northern Virginia during the Gettysburg Campaign. As Confederate troops advanced into Pennsylvania, they systematically abducted free black Pennsylvanians and sent them south into slavery. Contrary to the belief that these were the isolated actions of individual soldiers, historical records show that they were systematically carried out by Lee’s commanders at the brigade, division, and corps level. This omission is demonstrated by Lee’s interaction with his trusted aide Walter Taylor (Bo Brinkman) in a deleted scene in which he responds to Taylor’s report of local civilians’ complaints about food confiscation by declaring, “This army will conduct itself properly, and with respect to all civilian populations at all times.” Historically, while Lee issued orders for his troops to behave courteously toward white Pennsylvanians they encountered, this did not extend toward African Americans who were abducted by ANV units, and even in their interactions with white civilians, Confederate troops did not always conduct themselves accordingly, as they confiscated food and livestock, for which they paid in worthless Confederate dollars. Furthermore, there were a series of recorded instances of hostile interactions between Confederate troops and white Pennsylvanian civilians, as many Confederates relished the opportunity to bring the war into the North after their experiences fighting the Army of the Potomac in Virginia, while Pennsylvanians in turn saw the Confederates as invaders, with African Americans facing a very real threat of capture and enslavement. Consequently, this deleted scene between Lee and Taylor provides a misleading impression of the ANV’s treatment of Pennsylvania civilians during the Gettysburg Campaign, which historically was not always honorable.

While the film’s balanced portrayal of both sides serves to capture the complexity of each of the leading characters, its romanticization of their heroism also obscures certain facts about their wartime careers which were more nuanced. This is particularly true of the portrayal of George E. Pickett (Stephen Lang), the dashing and flamboyant division commander whose epic charge on July 3rd became an iconic hallmark of the battle. Overall, Pickett is depicted as a tragic character whose enthusiasm and desire for glory results in the destruction of his division, after which he tearfully answers Lee’s instructions to reform by replying, “General Lee, I have no division.” The epilogue states that Pickett “survives the war to great glory, but broods on the loss until his dying day.” Historically, however, Pickett became a figure of controversy in February 1864, following his execution of twenty-two North Carolinians who had defected to the Union Army at Kinston, North Carolina, for which he was accused of war crimes. Due to the intervention of his old West Point friend Ulysses S. Grant, Pickett never faced trial, and the Kinston incident was obscured in the following years by the mythologization of Pickett’s Charge. In addition, Pickett’s reputed glory was also undermined by his inept conduct at the Battle of Five Forks in April 1865, in which he attended a shad bake with his staff while his division was routed by Phillip Sheridan’s cavalry, which reportedly prompted Lee to remark, “Why is that man still with this army?” Therefore, Pickett’s historical record as a military commander sharply contradicts the epilogue’s notes, which in some ways correspond with the Lost Cause narrative’s memorialization of Pickett.

In summation, Gettysburg is a superbly crafted historical epic which brilliantly captures the authenticity of the Battle of Gettysburg, but its omissions of certain aspects of the Gettysburg Campaign leave plot holes in the narrative for viewers who may take interest in a more detailed and comprehensive portrayal. While the focus of the film is on the experiences of the leading characters in the battle itself, these omissions can furnish a potentially misleading representation of the events of the campaign. In addition, some viewers may take issue with the film’s romanticization of the lead characters on both sides since they might see parallels with the Lost Cause narrative’s emphasis on Confederate heroism. Viewing this film from the lens of thirty years later, considering the current debate over Confederate monuments and memorials, will provide audiences with an opportunity to bring an informed and nuanced perspective to the film’s portrayal of one of the most pivotal events in Civil War history.

Leave a Reply