When we think of the great military accomplishments of Ulysses S. Grant, the capture of three Confederate armies at Fort Donelson, Vicksburg and Appomattox instantly comes to mind. After these, the great battles of Shiloh, Chattanooga and the Overland and Petersburg campaigns are usually cited. Nowhere on these lists will you find the battle of Belmont fought on November 7, 1861. Does this mean we should dismiss Belmont as a minor, insignificant engagement? I would argue “no” and this talk is my argument to support that conclusion. I’ll let you be the judge as to whether or not I have made a good case on behalf of this battle fought on Missouri soil.

Of all the battles fought by Ulysses S. Grant during the Civil War, there were two regarding which he showed marked sensitivity to criticism. One was the battle of Shiloh and whether or not he was surprised there on the first day. The other was the battle of Belmont, a relatively minor engagement when compared to his later battles. Belmont was Grant’s first Civil War battle, and its importance belies the small number of troops engaged or the casualty list.

This talk will address the circumstances leading up to the battle, provide an overview of the battle itself, and look at the subsequent controversies and Grant’s defense of his actions there.

On October 20, 1861, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant wrote a letter to his wife Julia from his headquarters in Cairo, Illinois. In it Grant discussed some personal matters and then went on to express his frustration at his forced military inactivity due to having to scatter his troops to defend several key fixed points. He also expressed his regret over having insufficient manpower to advance against the Confederate stronghold at Columbus, Kentucky. His frustration was summarized by the words “What I want is to advance.” He would soon get his wish.

After serving as Colonel of the 21st Illinois Infantry Regiment for approximately seven weeks, Grant was appointed a brigadier general of volunteers on August 9, 1861. He was then assigned to command Union forces first in Ironton and then in Jefferson City, Mo.

On August 28, 1861, Grant was assigned to command the District of Southeast Missouri by Major General John C. Fremont, commander of the Department of the West. (SHOW SLIDE) The district included most of southeast Missouri and southern Illinois, two areas that appeared to be threatened by Confederate forces. In response to these perceived threats, Union forces were being significantly increased in Grant’s district. Grant was pleased with his new assignment, telling Julia in a letter that it was third in importance in the country and adding that “General Fremont seems desirous of retaining me in it.” (SHOW FREMONT SLIDE) (Interesting historical footnote-Fremont ran against James Buchanan in the 1856 presidential election. Fremont lost the election and one of the votes against him was cast by one Ulysses S. Grant. Grant voted for Buchanan, allegedly saying “I voted for Buchanan because I didn’t know him and voted against Fremont because I did know him”).

Taking up his new command, Grant established a temporary headquarters in Cape Girardeau, Mo. on August 30, 1861. A few days later he moved his headquarters to the strategically key town of Cairo, Illinois. (SHOW CAIRO SLIDE) Cairo, located at the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, was thought to be the key to Federal control of the Upper Mississippi Valley and the natural control point for defense of the region. In addition, it could serve as a natural stepping off location for Union offensive operations along the rivers in the area.

Complicating Grant’s command assignment was the fact that the state of Kentucky was just across the two rivers from Cairo. Kentucky had declared itself to be a neutral state and had prohibited Union and Confederate troops from entering the state. President Lincoln was concerned that any violation of the neutrality by Union forces would push Kentucky into joining the Confederacy, a move which he deemed to be possibly fatal to Union hopes of victory. He was quoted as saying, “I hope to have God on our side in this war, but I must have Kentucky.”

The delicate balance act ended on September 3, 1861 when Confederate forces entered Kentucky and occupied the town of Columbus, approximately 18 miles south of Cairo on the Mississippi River.

Realizing the political implications of this armed violation of neutrality, Grant wrote the following letter to the Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives, “I regret to inform you that Confederate forces in considerable number have invaded the territory of Kentucky and are occupying and fortifying strong positions at Hickman and Chalk Bluffs (Columbus).” (For this Grant was reprimanded by Fremont for having communicated with state officials- that was Fremont’s purview).

In response to the Confederates’ violation of the state’s neutrality, the Kentucky legislature met the next day and declared their support of the Union war effort.

The door to Kentucky having been opened courtesy of the enemy, Grant wasted no time in walking through it. He sent troops to occupy another key town, Paducah, Kentucky, the site of another junction of two vital rivers, this time being the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers. Not stopping there, Grant also sent troops to occupy Smithland, Kentucky, where the Cumberland River flows from the Ohio. These two rivers would prove to be strategic invasion routes into the Confederate heartland and their points of origin were now firmly held in Grant’s hands, never to be relinquished.

Thus, even during this early stage of the war, Grant was demonstrating the strategic vision which would become a hallmark of his generalship.

Having secured the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, Grant next turned his attention to the two main concerns within his district. These were clearing southeast Missouri of Confederate forces and securing control of that section of the Mississippi River that was located within his command sector. To achieve the latter goal he would have to neutralize the formidable works constructed at Columbus, Kentucky.

After having seized the site in September, the Confederates under Major General Leonidas Polk had made it the most heavily fortified point in North America. It sat on bluffs 150 feet high overlooking the Mississippi River. 140 cannon and approximately 17,000 Confederate soldiers constituted the garrison’s defense. It was with good reason that Columbus was called “The Gibraltar of the Mississippi.”

Polk also established a small post at Belmont, Missouri, directly across the river from Columbus.

Grant, with approximately 20,000 troops scattered over his district, could not hope to directly assault such a formidable position. This did not stop him from asking permission on three occasions to threaten Columbus, this permission being denied by the St. Louis headquarters.

In late September, General Fremont took to the field and led a large army towards Springfield, Mo. with the purpose of destroying a Confederate army led by Major General Sterling Price. Price had previously won victories at Wilson’s Creek and Lexington, Mo. and Fremont was eager to exact revenge and restore his damaged reputation with the Lincoln administration.

Perhaps fearing that Polk might send troops from Columbus to reinforce Price, Fremont ordered Grant on November 1 to send troops southward on both sides of the Mississippi in a demonstration towards Columbus. He was further instructed to avoid actual combat during these maneuvers.

Before Grant could initiate this movement however, he received new orders on the following day which changed the situation. He was now directed to send troops to supplement a force then pursuing Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson of the Missouri State Guard in southeast Missouri. Thompson had been campaigning in the vast swamps in that part of the state. His tactics had been so frustrating for Union troops chasing him that he had acquired the nickname “Swamp Fox of the Confederacy.”

Grant dispatched multiple columns with orders to converge on Thompson and destroy his forces.

In his revised report on the battle of Belmont, submitted more than 3 years after the battle (to be discussed later) and in his Memoirs, Grant claimed to have received a telegram on November 5 from the St. Louis headquarters informing him that Price’s army was being reinforced by troops from Columbus. He further claimed it directed him to start the previously ordered demonstration against Columbus. No record of this telegram has been found. General Fremont, who would have been the only person who could have ordered it, had been relieved of his command 3 days earlier. His temporary successor, General David Hunter, had not “set up shop” yet. Fremont’s permanent replacement, Major General Henry Halleck, was not appointed to the command until November 9. So there was no one in St. Louis with the authority to issue such a telegram.

In addition, Fremont’s Asst. Adjutant General, Captain Chauncey McKeever, through whom any orders would have been sent to Grant, said that no such telegram had been sent. He later stated that Grant had violated the order of November 1 to make a demonstration without actually attacking the Confederates.

It is probable that no such telegram existed and that Grant’s staff officers, who helped prepare the revised report, mistakenly thought such an order had been given, since Grant on November 5 had ordered subordinates to prepare for the demonstration that had been ordered on November 1. Grant probably relied on this revised report years later when he prepared his Memoirs.

Regardless, Grant prepared his troops for the demonstration against Columbus/Belmont. Troops from Paducah were also ordered to cooperate with Grant on the Kentucky side of the river.

Thus Grant’s attention was divided between two separate fronts; Columbus/Belmont and Jeff Thompson’s forces, placing great demands on his troop resources. (It later was discovered that Polk had not detached troops from Columbus but Grant had to rely on the available intelligence).

The next day, November 6, Grant set out from Cairo with 3114 men and 6 cannon to conduct the ordered demonstration. The U.S. Navy provided 4 troop transports and 2 timberclad gunboats, the Tyler and the Lexington. The flotilla anchored for the night on the Kentucky shore 9 miles south of Cairo. Grant’s stated intention was to “menace” Belmont and drive the Confederate contingent there out of Missouri. Since the only known orders he received had directed him to avoid actual combat, how Grant planned to accomplish this “menacing” without fighting is one of the mysteries of the campaign. I don’t think he meant to land his troops on either the Kentucky or Missouri shore, march the troops up to the Confederate works, thumb their noses at them and then re-embark and return to Cairo.

While anchored for the night, Grant later claimed that at 2:00AM on November 7 he received a message (not stated whether written or oral) from Colonel W.H.L. Wallace at Charleston, Mo. In it Wallace informed him that a reliable Union man had reported Confederate troops crossing the river from Columbus to Belmont for the purpose of cutting off Union forces under Colonel Richard Oglesby. Oglesby had been ordered by Grant to march his troops in the direction of Belmont. (It is interesting to note that, again, no evidence of this 2:00AM message has been found in any contemporary documentation and historians have questioned its authenticity. (Wallace later stated that he knew nothing of such a message). Another of the enduring Belmont mysteries.

Regardless of whether he had received the message or not, Grant made a decision to turn the ordered demonstration into an actual assault on Belmont. His justification was twofold: 1) to protect the flank of Colonel Oglesby’s column and to prevent Polk from sending reinforcements to Price or Thompson and 2) find an opportunity to fight. Both Grant and his troops had been showing growing impatience to strike a blow for several months. The volunteer soldiers had enlisted to fight the enemy, not to merely drill and target practice against inanimate objects.

In his memoirs, Grant said “I had no orders which contemplated an attack by the National troops, nor did I intend anything of the kind when I started out from Cairo; but after we started I saw that the officers and men were elated at the prospect of at last having the opportunity of doing what they had volunteered to do-fight the enemies of their country. I did not see how I could maintain discipline, or retain the confidence of my command, if we should return to Cairo without an effort to do something.” Plainly, everyone was itching for a fight and Grant meant to find one.

Keep in mind that due to sketchy intelligence, Grant did not know the strength of the Confederate force at Belmont. That was not going to stop him however.

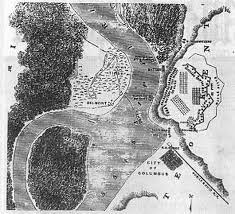

Early on November 7, the flotilla resumed traveling down the river and put to shore around 8:00AM at Hunter’s Farm on the Missouri side, approximately 2 miles northwest of Belmont. (SHOW MAP). Grant posted around 350 men to guard the transports and to serve as a reserve force if needed. He then marched the balance of his command, consisting of two brigades, about one mile and positioned them on the edge of a cornfield. Skirmishers were sent forward who soon made contact with Confederate cavalry patrols who had been alerted to the Federal troop landing. The Southern horsemen quickly fell back and met up with 5 Confederate infantry regiments which had been dispatched by Polk from Columbus to reinforce the Belmont garrison of 700 troops. Commanding this force was Brigadier General Gideon Pillow. (SHOW PHOTO/GIVE BIO)

-Commander of Tennessee’s troops at the outset of the war

-Had been a close personal friend of James Polk, used this connection to receive a brigadier general’s commission in the Mexican-American War

-During this war, he achieved a reputation for two things: overbearing arrogance and military incompetence-He gained notoriety for building entrenchments backwards

-Was court-martialed by Winfield Scott for insubordination and other charged/he was acquitted

-The one Confederate general for whom Grant showed open contempt

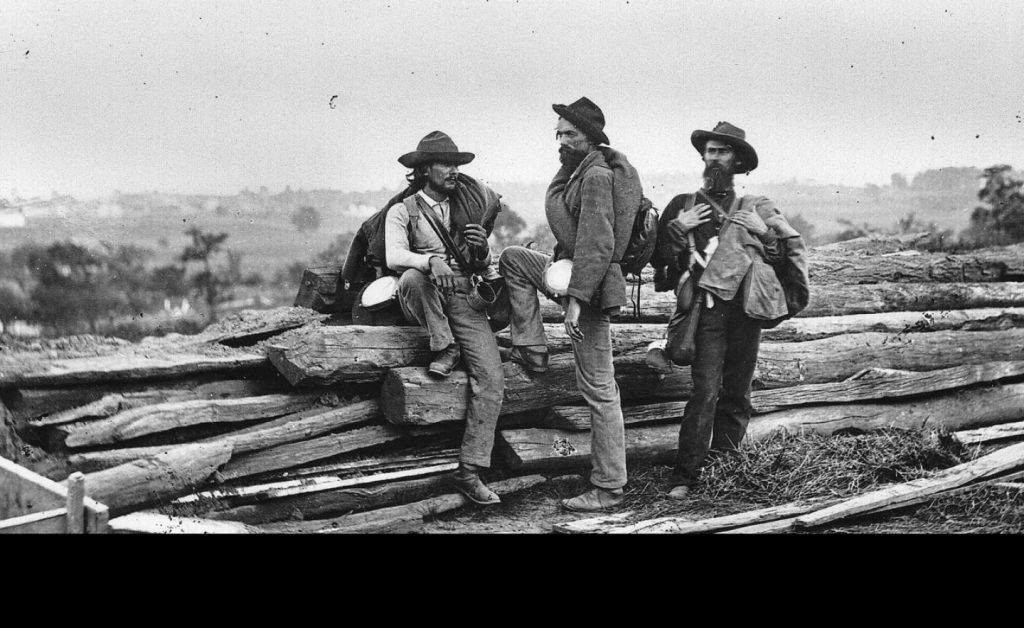

Grant’s and Pillow’s forces were roughly equal in numbers as well as inexperience. This would be the first time most of the soldiers would hear shots fired in anger.

The Union troops advanced through the cornfield and entered a patch of muddy ground in front of a densely wooded area in which Confederate skirmishers were positioned. The Southern troops were steadily pushed back through the timber until they reached their main line of battle. The Union troops advanced into the woods and the fighting escalated in intensity. Grant, directing his troops close to the front line, had his horse shot from under him and quickly remounted on a staff officer’s horse. While this fighting was going on, the heavy guns at Columbus were lobbing shells into the Union lines adding to the chaos and confusion.

Seeing that he was losing the initiative, Pillow ordered two offensive thrusts which were stopped in their tracks. He then ordered a bayonet charge against the Federals who were concealed in the wooded area. The attack failed and the Confederates retired and attempted to regroup. The federal troops began overlapping the Confederates’ flanks causing them to retreat to their encampment (Camp Johnston) on the river bank where they took up new defensive positions.

The Union troops pursued the retreating Confederates and the fighting renewed causing substantial casualties. With their backs to the river, many Confederates retreated up the riverbank to avoid being captured. They were not pursued.

With the Confederates being cleared from their abandoned camp, the Federal troops lost all discipline and began rummaging through the tents for souvenirs. One of Grant’s brigade commanders, Brigadier General John A. McClernand, a former U.S. Congressman, gave an impromptu speech to the troops.

-Political general from Illinois

-Former member of U.S. Congress

-Pre- war acquaintance of Lincoln

-Prominent Democrat-Lincoln needed Democrats’ support for the war

-Known for 2 things- ego and ambition

-Would be a constant thorn in Grant’s side until relieved during the Vicksburg campaign

The Union bands played patriotic tunes as the American flag was raised over the captured camp. The Northern boys thought that they had done a great thing, and they felt like celebrating.

Grant attempted to restore order with no success, so he ordered the tents and abandoned equipment to be set on fire. This, plus shells from the Columbus batteries falling in their midst, put an end to the troops’ plundering and celebration.

Leonidas Polk watched from Columbus as his troops on the other side of the river retreated up the riverbank. Realizing that disaster stared him in the face, he placed 2 regiments into boats and sent them up the river to join the Confederate troops on the riverbank.

The 2 Confederate forces were reorganized By Pillow and moved inland to strike the Union forces. Grant now faced a precarious situation. The reorganized Confederate forces were between his troops and their transports and now it was he who faced a possible disaster.

At approximately 2:00pm, the Union forces, believing the fight was over, began a leisurely withdrawal towards their transports. Suddenly they were struck by the reinvigorated Confederates. Panic set in as the Union troops feared they were cut off from their transports. Some of his officers called on Grant to surrender to which he replied “We had cut our way in and could cut our way out just as well.” Intense fighting ensued during which Grant’s forces were indeed able to cut their way through to reach their transports at Hunter’s Farm. (SHOW CONFEDERATE PURSUIT SLIDE) The Confederates pursued and fired on the Federals while they boarded the boats. It was reported that Grant was the last Federal to leave the field, boarding a transport just before it departed from shore.

The transports returned to Cairo and the battle of Belmont was over. Grant had suffered 590 casualties (20% of his force) while the Confederates lost 641 men (13%). Both sides claimed victory, the Union for having driven the Confederates into initially retreating from the field and the Confederates for having forced Grant to beat a hasty withdrawal on his transports back to Cairo.

As details of the battle of Belmont were published in the North, Grant received criticism from some newspapers and other sources, mainly outside of the army, that the battle had been devoid of any positive results and had only resulted in unnecessary casualties.

(Criticisms of the battle largely disappeared until the presidential campaign of 1868, when Democratic newspapers revived the issue by criticizing Grant for having fought an unnecessary battle).

For the rest of his life, Grant exhibited a sensitivity to criticisms of Belmont and offered justifications for having fought there.

In the days following the battle, he wrote several messages and letters regarding the battle in which he stated that it was fought to prevent Confederate troops from being sent from Columbus to reinforce Price and Jeff Thompson (which hadn’t occurred).

On November 10, 1861, three days after the battle, Grant wrote his official report to the Adjutant General’s office in Washington. The contents of this report are unknown, for the report was replaced by a revised report submitted on June 26, 1865, a full 3.5 years after the battle but pre-dated November 17, 1861. In this revised report, the mysterious 2:00am message from Colonel Wallace appears for the first time. The report repeated Grant’s previously stated reasons for fighting the battle.

At the time this revised report was written, Grant was the nation’s hero and the chief military architect of victory in the Civil War. So why would he feel compelled to revise his report about a small battle that no one had given much thought to in the three plus years since it occurred?

Grant’s defense of his actions at Belmont continued when he wrote his Memoirs during the last year of his life. In it he stated, “Belmont was severely criticized in the North as a wholly unnecessary battle, barren of results, or the possibility of them from the beginning. If it had not been fought, Colonel Oglesby would probably have been captured or destroyed with his 3000 men. Then I should have been culpable indeed.” He added, “The true objects for which the battle of Belmont was fought were fully accomplished. The enemy gave up all idea of detaching troops from Columbus…The National troops acquired a confidence in themselves at Belmont that did not desert them through the war.”

So the question remains, why did Grant turn an ordered demonstration into an actual attack? And why was he so sensitive about criticisms of this relatively minor engagement? Regarding the first question, the late John Y. Simon, the foremost authority on U.S. Grant, concluded that it is impossible to reconcile the divergent interpretations of Grant’s motives in attacking Belmont. One theory is that Grant originally planned to land his troops on the Kentucky side to make a demonstration against Columbus while Colonel Oglesby’s troops moved on Belmont. The theory continues that Grant changed his mind and decided to attack Belmont upon learning that Oglesby was being menaced by troops from Columbus.

And what of the purported 2:00 AM message from Colonel Wallace which Wallace said he never sent? Did Grant make it up to justify disobeying orders not to make any attacks? Grant was a scrupulously honest man who couldn’t abide dishonesty in others so I think it’s safe to eliminate this possible explanation. Was his memory playing tricks on him when he cited the 2:00 AM message 3.5 years later when he wrote his revised report?

I believe he went to Belmont looking to force a fight and the alleged messages he received provided the pretext to start one.

As for Grant’s sensitivity about Belmont, perhaps it’s simply because it was his first battle commanding troops during the war. Grant received his share of criticism concerning his later battles and he did not feel the need to defend his actions as he did for Belmont. To again quote Dr. Simon regarding both of these points, “The answer must be found in U.S. Grant himself, and no simple answer will do.”

Finally, what benefits to the Union cause were derived from the battle of Belmont? The Union troops who fought there formed the nucleus of the Army of the Tennessee, arguably the most successful Union army of the war. The troops did indeed acquire a confidence in themselves that stayed with them throughout the war.

Grant acquired valuable experience as a commander at Belmont. He made his share of mistakes during the battle, but he learned from them. He also made mental notes concerning General Gideon Pillow, the principal Confederate field commander during the battle. This information came in handy three months later when the two generals faced each other again at Ft. Donelson.

Another interesting aspect of the battle of Belmont is that several later prominent Confederate generals also had their baptism of fire here. Polk and Frank Cheatham rose to corps command in the Army of Tennessee and Pillow became second in command at Fort Donelson before his incompetence and overbearing egotism became too much for President Jefferson Davis, who removed him from field service in 1862.

Belmont is also instructive in assessing Grant’s development as a military leader. In this small battle Grant first displayed the qualities that later became hallmarks of his generalship, namely aggressiveness, initiative and determination.

The calmness under adverse circumstances displayed by Grant at Belmont was shown on larger stages at Ft. Donelson, Shiloh, the Wilderness and elsewhere. The initiative in taking risks to bring the battle to the enemy he showed by attacking a Confederate force of unknown size at Belmont was repeated on a much grander scale during the Vicksburg campaign. And the determination to cut his way out of a potential trap when the Confederates placed themselves between his forces and their transports was the same determination he showed in pursuing Robert E. Lee’s retreating army and compelling their surrender at Appomattox.

Another interesting aspect of the battle involves the number of personal close calls Grant had. As previously stated, he had a horse shot out from under him during the early stages of the battle. Commanding his troops from just behind the battle line, Grant was constantly under fire. During the retreat to the transports, he was the last Federal to leave the field. Pursuing Confederates were maintaining a steady fire. A gang plank was extended from one of the boats to the shore which Grant rode his horse on to board the vessel. He then dismounted and went to the boat captain’s stateroom where he lay down on a sofa briefly to catch his breath. He no sooner had gotten up from the sofa when a bullet came through the wall of the room and lodged in the head of the sofa.

Thus the course of history could have been changed if a single Confederate bullet had been fired a little higher (when his horse was shot) or sooner (in the boat’s stateroom).

Interestingly, in her Memoirs, Grant’s wife Julia claimed to have had a vision of her husband on horseback facing great peril. When they met a short time later, they discovered that this vision had occurred at the exact time when Grant was riding under fire to board the transport.

This small engagement in Missouri was also an early indicator to President Lincoln that here was a general who fought, a quality he was looking for in his generals.

(Lincoln was becoming frustrated with the inactivity of his generals, which grew increasingly larger in the following months).

In conclusion, it could be said that the seeds of the great victories at Ft. Donelson, Vicksburg and Appomattox were planted in the rich, fertile Missouri soil of Belmont.

Leave a Reply