During General Robert E. Lee’s retreat from Gettysburg in early July 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) faced a dangerous period filled with challenges as it returned to Virginia. After three days of intense fighting at Gettysburg, Lee’s army began its retreat on July 4th and recrossed the Potomac River 10 days later, the evening of July 13th.

Lee’s retreat from Gettysburg was perilous and arduous, requiring a wagon train of hundreds of wagons extending 15 to 20 miles to traverse South Mountain while battling severe storms, poor roads, and Union cavalry raids. His army was vulnerable the entire time of his movement. Lee’s ability to protect his army during the retreat and avoid a major engagement with the pursuing Union forces allowed him to preserve much of his army’s strength for future campaigns in the Eastern Theater. It is one of the lesser-known moments of the war but displays the kind of resourcefulness that the ANV became noted for.

The Retreat

The evening of July 3rd, Ewell’s Second Corps was pulled back from Culp’s Hill through the town of Gettysburg and placed on Oak and Seminary Ridges. They built a perimeter in case Meade attempted an offensive operation. Lee sent his long train of 8000 wounded men, equipment and supplies first, with the infantry to follow. About 6,800 wounded were left behind as they were in no condition to travel.

The ANV began its retreat from Gettysburg the night of July 4in heavy rain. There were two possible routes Lee could choose for the retreat to take over South Mountain: Chambersburg Pike, which passed through Cashtown, was the original way his army entered the battle, and a shorter route moving southwest on the Fairfield Road toward Williamstown by way of Hagerstown. The ANV moved west and south while screened by Stuart’s cavalry. Most of the infantry was routed through Fairfield MD through Monterey Pass to Hagerstown.

The Union infantry began its movement July 5, the next day. As the map shows, rather than follow directly behind the two Confederate columns behind South Mountain, they took a more southern approach on the east side. From July 5-13, the Union forces converged on Middletown. Their idea was that they would be able to get to Hagerstown faster and use the gaps to the south to cross the mountain.

Rear Guard Defense

Meanwhile, as Lee’s army moved southward, they faced constant pressure from Union cavalry, leading to numerous skirmishes and engagements along the way. Confederate cavalry played a crucial role in delaying Union pursuit and protecting the retreating Confederate infantry.

During Lee’s retreat from Gettysburg, there were several skirmishes and minor engagements with pursuing Union forces. At least 5 encounters before Williamsport are given names and two others occurred after the eventual crossing of the Potomac. These skirmishes were small-scale battles characterized by relatively small numbers of forces engaging in limited combat. The goal of the Confederate rear guard was to slow down the Union advance and protect the retreating army, while the Union forces sought to disrupt and harass the Confederates as they withdrew.

Brigadier General John D. Imboden was placed in charge of this retreat. According to journal articles he wrote after the war, Lee met personally with him the early morning of July 4th and gave him orders to lead the ambulances, subsistence trains and cattle plundered during the campaign back to Virginia, with the active army in the rear as protection. His mission was to ensure the safe retreat of the Confederate forces. Imboden’s cavalry was responsible for safeguarding the lengthy wagon train, which stretched for miles and contained a significant amount of captured Union supplies and wounded soldiers.

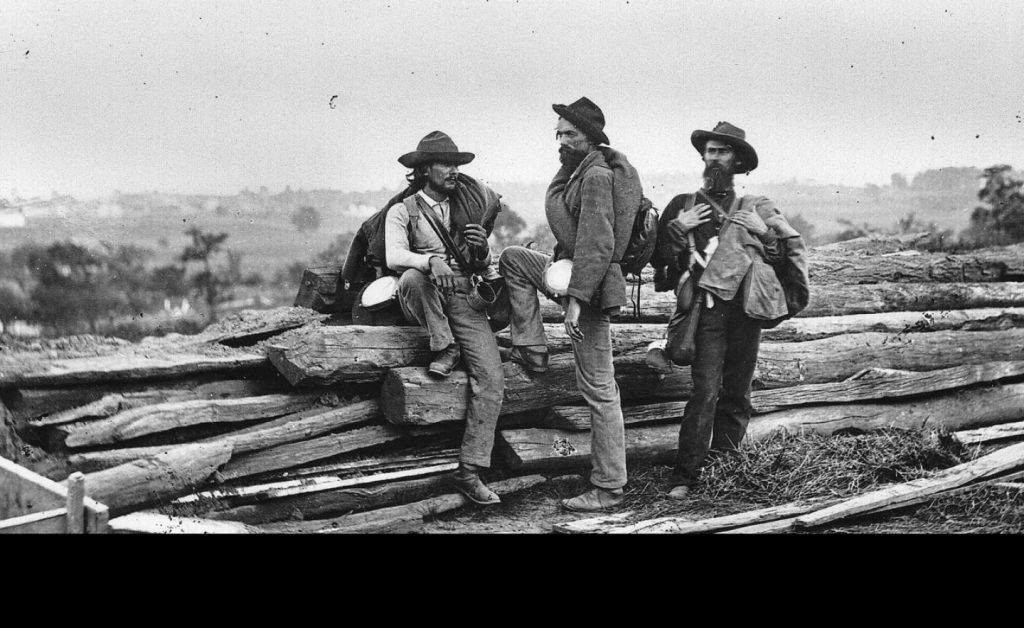

Brig Gen John Imboden

Imboden’s task was challenging as Union forces were in pursuit, and the Confederate army was low on provisions, making the retreat arduous and the need for protection critical. Despite the pressures of Union pursuit and potential attacks, Imboden managed to keep the wagon train relatively secure during the withdrawal, successfully guiding it through the challenging terrain and back to Virginia.

General Imboden played a crucial role in providing support and organization to the Confederate forces as they withdrew from Pennsylvania and headed back to Virginia. His cavalry command was instrumental in guarding the Confederate wagon train, which was essential for transporting wounded soldiers, supplies, and equipment. His efforts allowed the Confederate army to regroup and recuperate, preserving its fighting strength for future engagements. While the retreat from Gettysburg was a difficult and disheartening experience for the Confederate forces, Imboden’s contributions in ensuring the safe passage of the wagon train played a significant role in sustaining the army’s ability to continue the war effort in subsequent campaigns.

Imboden’s cavalry command was not highly regarded within the ANV. Stuart had not taken them on his circumnavigation ride. Imboden was reinforced with artillery and other cavalry units, and ordered to depart from Cashtown, turn at Greenwood to avoid Cashtown (see map) and head for Williamsport.

The Journey

To buy time for the main body of the Confederate army to cross the river safely, Imboden’s cavalry engaged in skirmishes and delays against Union forces that were in pursuit. This delaying action allowed Lee’s army to reach Williamsport and begin constructing makeshift bridges and pontoons to facilitate the river crossing. Imboden began constructing defensive works. Meanwhile the Union army pursued over non-mountain roads to the east of Lee’s route.

Severe storms and rains began the day of July 4th and continued as the wagon train started its movement. Imboden’s orders were to not stop for any reason, so wagons or critically wounded men who could not travel further were left behind. On July 5th, as he passed through Greencastle, civilians attacked the train with axes and had to be driven off. Later that day at Cunningham’s Crossroads, a Union cavalry force attacked resulting in hundreds of prisoners, many of them wounded.

On July 6, Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick‘s cavalry division attacked the rear guard. They chased two cavalry brigades through the town of Hagerstown. When the main body of Stuart’s cavalry arrived, they were outnumbered and withdrew.

Battle of Boonsboro (July 8, 1863): As the retreat continued, Union cavalry again clashed with Confederate forces under General J.E.B. Stuart near Boonsboro, Maryland. This skirmish was part of the ongoing efforts to delay the Union pursuit. Stuart encountered the Union cavalry under Generals Judson Kilpatrick and John Buford at Beaver Creek Bridge. Kilpatrick’s salient proved weakest, but Stuart was unable to take advantage when Union infantry arrived to reinforce the line. Although neither side gained ground, Stuart succeeded in delaying the pursuit.

Battle of Funkstown (July 10, 1863): After crossing the Potomac River into Maryland, Confederate forces under General J.E.B. Stuart engaged Union cavalry under General John Buford near Funkstown. The skirmish was part of a series of actions as Lee’s army moved southward, with the Confederates attempting to delay the Union pursuit. A brigade under the command of Colonel Thomas Devin attacked Stuart’s forces,who were arrayed in a crescent shaped 3 mile line. The battle was a relatively minor engagement, and the primary objective for both the Confederate and Union forces was to protect their respective positions and avoid significant losses.

Neither side could claim a clear victory, although Stuart succeeded in delaying the Union pursuit. The skirmish saw intermittent fighting, but neither side launched a full-scale assault or made significant gains. The Confederates managed to hold their ground and fend off the Union cavalry’s attempts to dislodge them, while the Union forces were unable to make a breakthrough.

Williamsport

The retreating Confederate troops and ambulance train advanced toward Williamsport, expecting to cross over the pontoon bridge they had constructed to get to Maryland Lee had not been informed that a cavalry raid on July 4 had destroyed the pontoonbridges they had used to cross on their way to Gettysburg. Union cavalry dispatched from Harpers Ferry had destroyed the Confederate pontoon bridge across the river at Falling Waters.Moreover, there had been many days of rain after the battle, causing the Potomac River to rise as much as 10 feet. Only a single small ferry was available for crossing. The Confederate Army found itself trapped by the impassible Potomac.

The Battle of Williamsport is also called the Battle of Falling Waters and the Battle of Hagerstown, which makes it confusing to follow. Falling Waters was the location of the pontoon bridge, located at the tip of a bend in the river (see map). Williamsport was the town just north and west of it, and Hagerstown was the larger crossroads town north of Williamsport.

Map of the Vicinity of Hagerstown, Funkstown, Williamsport and Falling Waters. Library of Congress. Union Army in blue, Confederate Army in Red.

When he arrived in Williamsport on July 6, Imboden found the bridge out, the fords impassable, and no way to get over the river. He was in essence, trapped between the river and the Union Army. Expecting an attack, he constructed a defensive perimeter along the crest of a ridge about one-half mile from Williamsport at Falling Waters. Imboden formed a defensive position anchored on his left by the Conococheague Creek and on his right by the Potomac River.

He assembled a make-shift defensive force that included an artillery battery and as many of the wounded who could operate muskets because there were insufficient healthy soldiers around to man the defenses. Imboden asked his wagon drivers to join the fight with walking wounded, and over 600 volunteered. This hurriedly organized force resisted attacks from Union cavalry led by John Buford and Judson Kilpatrick on July 7th, saving the wagon train. Buford arrived east of Williamsport, flanking the town. Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick took a different route that took him down the main road. Kilpatrick’s cavalry chasedtwo Confederate cavalry brigades through Hagerstown before being forced to retire by the arrival of the rest of Stuart’s command. Imboden fooled the enemy by advancing a line of infantry about 100 yards beyond the crest of the ridge and then slowly pulling the men back out of sight. Finally General Fitz Lee’s cavalry arrived and the Federals were driven off.

The Confederate infantry reached the Potomac River ford at Williamsport on July 8 and 9. On July 11, Lee entrenched a lineto protect the river crossings at Williamsport, anticipatingMeade’s army to advance. On July 12 & 13, Meade probed the Confederate line, with heavy skirmishing. Meade prepared his forces for an attack. On the morning of the 14th, Kilpatrick’s and Buford’s cavalry divisions attacked Henry Heth’s rearguard division on the north bank, taking more than 500 prisoners. Confederate Brigadier General James Pettigrew was mortally wounded in the fight.

The defense was so formidable that despite Halleck, Stanton and Lincoln demanding a battle before Lee got away, Meade would not attack a position so strong that he believed it would be akin to Marye’s Heights. General Lee traditionally receives the credit for this 9-mile defensive line, and indeed he and his engineers developed a fantastic perimeter fronted by rain-flooded fields. Lee set up the line with artillery placing any attack in crossfire. Meade was right; it would have been insane to try. Meade chose not to attack Lee in his trenches, believing the position could not be successfully breached.

General James Johnston Pettigrew’s Death

On the morning of July 14, Kilpatrick’s and Buford’s cavalry divisions approached from the north and east respectively. Before allowing Buford to gain a position on the flank and rear, Kilpatrick attacked the rearguard division of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth, taking more than 500 prisoners. Confederate Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew was mortally wounded in the fight.

On July 14, Confederate forces under General Pettigrew were defending the crossing at Falling Waters, where they encountered Union troops. During this engagement, Pettigrew was severely wounded and taken from the field for medical attention. Unfortunately, his injuries were severe, and he died from his wounds on July 17, 1863. His death was a significant loss for the Confederate army, as he was a talented and respected officer.

Aftermath

During this time period the river fell adequately so a new bridgecould be constructed. Lee’s army began crossing the river after dark on July 13th. Most of Lee’s forces crossed on July 14th.

On July 16, Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg’s cavalry nearShepherdstown engaged in a battle with the brigades of Brig. Gens. Fitzhugh Lee and John R. Chambliss, supported by Col. Milton J. Ferguson’s brigade positioned to hold the Potomac River fords. Fitzhugh Lee and Chambliss attacked Gregg, who resisted against several attacks until he withdrew..

On July 17, 1863, the last of Lee’s troops safely crossed the Potomac River back into Virginia, officially concluding the retreat from Gettysburg. Union forces did not pursue the Confederates into Virginia, and the campaign ended with the Confederate army regrouping south of the Potomac. The retreat was complete at the end of July with both armies on either side of the Rappahannock River, once again in an even position.

Critical Assessments

Despite the tenacity of the Union pursuit, General Lee’s skillful use of his cavalry and the tenacity of his infantry allowed him to protect most of his army during the retreat. As a result, Lee’s army managed to regroup in Virginia, ensuring its continued ability to engage in further campaigns in the Eastern Theater of the Civil War. Kent Masterson Brown concluded that Lee’s successful retreat maintained the balance of power in the eastern theater and left his army with enough forage, and supplies to ensure its continued existence as an effective force.

Imboden’s skillful leadership and actions during the retreat contributed to the preservation of the Confederate army’s fighting strength for future campaigns in the Civil War. General Imboden wrote a series of magazine articles after the war providing a first- hand account of these actions and his participation in them. The most widely quoted is his Battles and Leaders article of 1888, which has been criticized for overstating his own involvement. Jubal Early was especially critical of Imboden’s description of the pain endured by the Confederate wounded on the especially bumpy ride across the mountains.

Historical debates over General George G. Meade’s actions after the Battle of Gettysburg have led to different perspectives on whether he was in error for not more aggressively pursuing and attacking Lee’s retreating army. Some historians and military experts have critiqued Meade’s decisions but most modernhistorians defend Meade’s cautious approach, emphasizing the challenges he faced in assessing the situation accurately and making informed decisions amid the aftermath of a grueling battle.

Whether or not Meade missed an opportunity to deliver a decisive blow to Lee’s army isn’t clear. The failure to pursue Lee vigorously was seen by some as a missed chance to deal a knockout blow to the Confederacy, including at the time, President Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton. Some believe that a more aggressive pursuit and attack could have potentially weakened or dispersed Lee’s forces further, leading to a more significant strategic advantage for the Union. However, losses to Union forces at Gettysburg, including its officer corps, was profound. It also must be remembered that Meade had only been commander in chief for less than a week.

Some argue that Meade’s cautious approach was based on strategic considerations, such as concerns about Confederate reinforcements or the need to secure his lines of communication and supply. While a pursuit could have led to an offensive advantage, it also posed risks to the Union’s own position and logistics. Both Brown and Wittenberg agree that any attempt to attack Lee’s position at Williamsport would have led to disaster.Critics contend that Meade’s caution and hesitancy to launch a full-scale pursuit demonstrated a lack of confidence and assertiveness in his leadership. Often citing Ulysses Grant, they argue that a more assertive commander might have capitalized on the Union victory at Gettysburg and pursued Lee more aggressively.

References

• Imboden, John. The Confederate Retreat from Gettysburg. In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, volume 3, pages 420-429. New York, The Century Company, 1887-1888.

• Brown, Kent Masterson. Retreat from Gettysburg: Lee, Logistics, & the Pennsylvania Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

• Wittenberg, Eric J., J. David Petruzzi, and Michael F. Nugent. One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, July 4–14, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie, 2008.

• Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; A study in command. New York: Scribner’s, 1968.

• Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003

• Klein LW. Brigadier General John Imboden. https://www.rebellionresearch.com/brigadier-general-john-imboden

• https://ehistory.osu.edu/biographies/john-daniel-imboden-defender-valley

• https://www.hollywoodcemetery.org/john-d-imboden

• Klein LW. General George Meade After the Battle of Gettysburg.

• https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ah-gettysburgcampaign/

• https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/battle-of-williamsport/

Leave a Reply