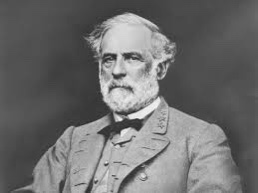

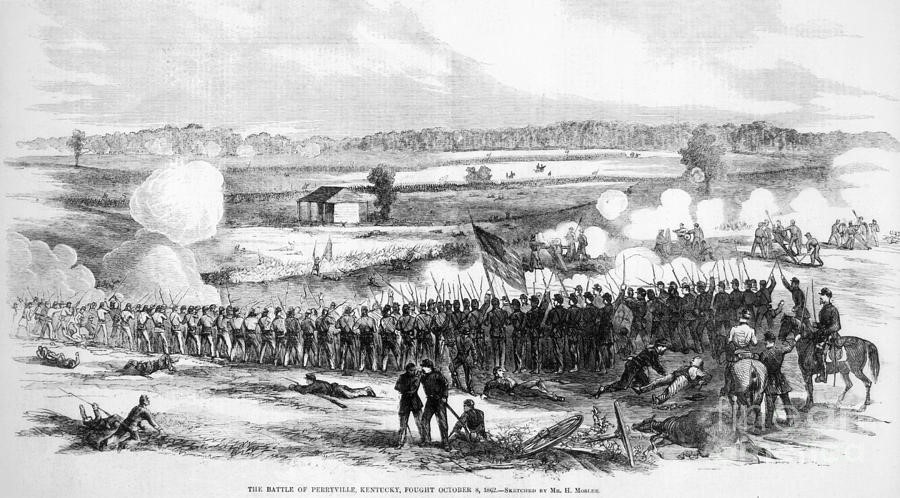

Late in the afternoon of July 1, 1863, after a full day of fierce fighting, Confederate troops had driven the Union defenders from the fields west of Gettysburg. As the Union troops fled through the town east toward Cemetery Hill, General Robert E. Lee sent a discretionary order to Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell, meaning he left the decision of whether to make a late attack to Ewell’s judgment.

In the late afternoon and evening of July 1, after the Confederate victory on the first day of the battle, Ewell’s troops had the opportunity to attack and potentially seize Culp’s Hill, a key position in the Union defensive line. Ewell, after assessing the situation and considering various factors such as the approaching darkness, the strength of the Union defenses on Culp’s Hill, and the absence of clear orders from Lee to attack, decided against launching an immediate assault. Instead, he chose to consolidate his positions and wait for further instructions.

The decision by Ewell not to attack Culp’s Hill has been a subject of historical debate and criticism ever since, as some argue that seizing that high ground could have potentially changed the outcome of the battle. This order and its aftermathhad significant implications for the outcome of the battle. And, it’s a window into Lee’s thoughts about being engaged in a battle on July 1 he didn’t plan. Legend tells us that, at that crucial moment, Ewell lost his nerve. Instead of pursuing the fleeing Union soldiers, who were so panicked they could not defend themselves, Ewell held back, allowing the Federals to entrench atop Cemetery Hill. Lee had just arrived on the field and saw the importance of Cemetery Hill. Historian James M. McPherson wrote, “Had Jackson still lived, he undoubtedly would have found it practicable. But Ewell was not Jackson.” Ewell chose not to attempt the assault. The advantage of holding the heights led to the Union victory at Gettysburg.

Ewell’s indecision at that crucial moment supposedly cost the South the battle, and the war. But was that the reality?

The Order & The Situation

According to Walter Taylor, Lee was told of Ewell’s movements by Major G. Campbell Brown of Ewell’s staff. He then instructed Brown:

‘To quote Lee’s own words, “General Ewell was…instructed to carry the hill occupied by the enemy, if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army…” ‘

From Freeman, Douglas Southall. Lee’s Lieutenant’s: AStudy in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.571

How do we know these were Lee’s precise words? No written copy of Lee’s order exists, for the simple reason that, by that stage of the war, Lee rarely put orders in writing. After the infamous lost cigars incident that preceded Antietam/Sharpsburg, Lee was ever mindful of the fact that written orders could get lost, and that such a circumstance had the potential to lead to disaster, so he generally preferred to give his orders verbally. And so, this order was transmitted verbally by courier, and remembered by Taylor years later (in his memoirs and in several Southern Historical Society Papers). Sothis after battle report does comport with Walter Taylor’s post war recollections. But he also claims to have been the one who delivered it, which has been questioned.

Lee habitually issued discretionary orders with varying degrees of effectiveness. With Stonewall Jackson, a man of ruthless battlefield instincts, Lee was able to get away with this, even when Lee’s intent was less than clear, but even with Jackson such orders occasionally went awry as was the case during the Seven Days. Lee’s aide Walter Taylor noted that Jackson “took the suggestion of General Lee into immediate consideration, and proceeded to carry it into effect.” This was not to be the case with corps commanders who followed Jackson, something that Lee failed to adjust to that would contribute to the fate of his army at Gettysburg. The fact that 2 of his 3 corps commanders at Gettysburg were new to that level of command is highly relevant to what happened on July 1. AP Hill’s advance on the town with Heth in command was a novice’s error, in retrospect. Stonewall Jackson would not have made the mistake of walking into General Buford’s command blindly.

Ewell did not get that message until after his forces were heavily committed, noting in his report “that by the time this message reached me….It was too late to avoid an engagement without abandoning the position already taken up.” Ewell seemed to believe he forces were too understrength, the Union forces too large, or the position of the hills south and east of the town was too strong to be taken at that time. He sent a courier to Lee and Hill requesting a simultaneous assault from Hill to the west and his forces from the north, and another courier to Johnson to continue his approach until at the front, halt and await orders.But Lee responded that Hill would be unable to assist in any assault that evening.

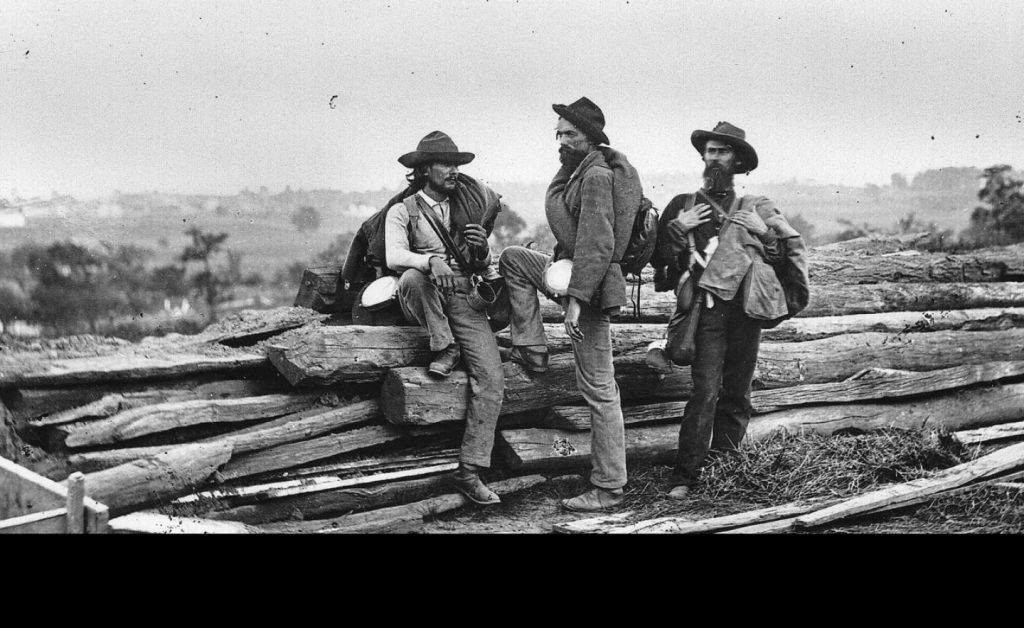

In fact, at that moment, although victorious, his corps had suffered approximately 3,000 casualties, leaving him with about 8,000 men under arms. The charge into Gettysburg had also left Ewell’s two divisions badly disorganized, and there were thousands of prisoners that had to be rounded up and secured. The third division, under Edward Johnson, was rushing to the scene, but no one knew when it would arrive.

What is the Intent Behind Issuing Discretionary Orders?

Discretionary orders are important to the success of commanders who desire that their subordinates have the necessary freedom to exploit opportunities within the broader operational context. They are a key element of what we now define as Mission Command. To be effective such orders need to be clear and concise and they must be employed in a manner that are within the capabilities of one’s subordinate commanders to both understand them and carry them out. Thus, a commander must always be ready to adjust his method when his command goes through a major turnover of personnel.

Discretionary orders were customary for General Lee because Jackson and James Longstreet, his other principal subordinate, usually reacted to them very well and could use their initiative to respond to conditions and achieve the desired results. Lee probably erred if he wanted Ewell to attack under any circumstances. But he never gave Ewell a peremptory order, so we can only guess. It isn’t exactly clear even 160 years in retrospect exactly what Lee intended and to be fair, Ewell in the heat of the moment couldn’t figure it out either.

To “…avoid a general engagement…”

By allowing Hill’s Corps to march into Gettysburg, an entire corps was already engaged by 11 am. Lee was not happy that battle had been joined by Heth. Taylor observed that “on arriving at the scene of the battle, General Lee ascertained that the enemy’s infantry and artillery were present in considerable force” and when Lee arrived on Herr Ridge, Heth asked permission to renew his attack when Rodes entered the fight. Lee’s initial response was :“No, I am not prepared to bring on a general engagement today. Longstreet is not up.”

After observing the battle for a time, it became evident that Ewell’s corps was also heavily engaged and Lee began to change his mind, especially as his forces outnumbered the union forces up to that point and were carrying the day. Heth reported that the Federal troops in front of him were withdrawing and Lee sensed an opportunity to strike a blow that might bring the climactic victory that he sought. Lee analyzed the situation and with Heth back at his division Heth wrote that: “very soon an aide came to me with the orders to attack.”

Lee had instructed Brown to convey to Ewell that a general engagement should be avoided until the arrival of the rest of the Confederate army. By ordering Ewell not to bring on a general engagement, it is strongly suspected that Lee intended to maintain a defensive posture and avoid risking a full-scale battle until the Confederate forces were consolidated and had greater numerical strength. This means operationally that he wanted Longstreet up, and Lee wanted to ensure that the Confederate army was in a more favorable position and had the support of their entire force before committing to a major confrontation with the Union army. Lee noted in his after action report that “It had not been intended to deliver a general battle so far from our base unless attacked…”.However, Ewell did not receive this message in time and his forces became heavily engaged in battle before the communication reached him. As a result, Ewell felt that it was too late to disengage without abandoning the position his forces had already taken up.

When Ewell’s third division, under Maj. Gen. Edward”Allegheny” Johnson, arrived on the battlefield, Johnson was ordered to take the hill if he had not already done so. Johnson did not take Culp’s Hill. He sent a small party to reconnoiter, and they encountered the 7th Indiana Infantry of the I Corps, part of Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth’s division, which had been in the rear guarding the corps trains and was now linked up with the Iron Brigade, digging in following their fierce battle on Seminary Ridge. Johnson’s party was taken by surprise and almost taken prisoner before fleeing. Culps Hill at 7 pm when the reconnaissance occurred was far from empty. Was it empty at 5 pm? No but less well defended; still, who would Ewell have attacked with? After the war Gordon said in his memoirs he was ready, but he’d seen significant action. And as Pfanz notes, Gordon’s brigades were scattered and 2 miles from where an attack could be made. And the 11th Corps troops on Cemetery Hill under Howard were well positioned to defend Culps hill, more so than Ewell was positioned to take it. There would have been a fight no matter what, the difference is whether you are just fighting the tired remnants of the troops you had already fought earlier or brand new troops (Candy’s brigade + possibly 12th Corps).See Pfanz Culps Hill and Cemetery Hill pages 76-79.

In his report of the battle, Lee only briefly touched on the subject when he wrote, “General Ewell was … instructed to carry the hill occupied by the enemy if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army which were ordered to hasten forward. He decided to await Johnson’s division [but it] did not reach Gettysburg until a late hour.”

But, there are no reports indicating that he urged caution on his commanders not to bring on a general engagement before the battle was already underway. And at that point, 2 of his 3 corps had been heavily engaged; if day 1 wasn’t a general engagement, what is? And Lee must have grasped that there was already a major engagement under way all day; so, what did he expect Ewell to do when he received that order?

“…to carry the hill occupied by the enemy, if he found it practicable …”

The orders from Lee contained an innate contradiction. Ewellwas to carry the hill occupied by the enemy, if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army.

Ewell’s professional opinion on receiving Lee’s order to carry the hill “if practicable” was that the attack, in fact, was not practicable under the existing circumstances. The Confederates charged the hill multiple times in the next two days, ultimately failing. This has led to over a century and a half of doubt about that original decision. Ewell’s record before that day and after have been minutely studied for evidence that he had lost aggressiveness after his leg amputation and marriage, and perhaps in retrospect PTSD; and of course, the counterpoint, that had Stonewall Jackson been alive, he would have been the one making this decision, and as suggested by McPherson, we all “know” Jackson would have attacked, taken the hill, and the battle of Gettysburg would have been over.

But suppose Ewell found the two parts of the order were in conflict? Lee’s order to Ewell contained not one, but two caveats. Not only did the order say to take the hill “if practicable,” it also said to take the hill only if it could be done “without bringing on a general engagement.”

Shelby Foote indicates that the order directed Ewell “to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army.” It is known that Ewell sent to Lee to provide support for the movement from other corps but was told that could not be done. Lee could not provide assistance that Ewell requested from the corps of A. P. Hill. Ewell’s men were fatigued from their lengthy marching and strenuous battle in the hot July afternoon. It would be difficult to reassemble them into battle formation and assault the hill through the narrow corridors afforded by the streets of Gettysburg. It may well be that Ewell deduced that therefore, he could not fulfill the conditions of the order.

Critique of Ewell’s Reaction to the Order

Lee’s orders to Ewell, to take the high ground “if practicable” were probably correctly interpreted by Ewell despite his critics; the nature of the terrain, the number and condition of the troops that he had available for an attack, and the nature of the orders given by Lee late in the day was strong factors for Ewell to not attack. Coddington noted that these problems “upset Ewell, for he was faced with the prospect of organizing a new attack with tired men even while he felt constrained by Lee’s injunction not to open a full-fledged battle.” No wonder he was uncertain. The fact that Lee was not far away and did not issue a “peremptory order to Ewell” to attack also has to be noted. If Lee had sensed that Ewell was not going to attack and really wanted him to he could have issued a direct order which Ewell would have surely obeyed.

2) Culp’s Hill was so significant because it guarded the main Union supply line on the Baltimore Pike and the rear of the Union army on Cemetery Ridge.

In the face of this discretionary, and possibly contradictory, order, Ewell chose not to attempt the assault. The three main reasons most often given include: 1) the battle fatigue of his men in the late afternoon, as his men had marched a great distance and were exhausted 2) the difficulty of assaulting the hill through the narrow corridors afforded by the streets of Gettysburg immediately to the north, and 3) that after the battle at Barlow’s Knoll and the attacks through the town, there had been enough casualties and mixing of lines to severely weaken command and control.

He might also have realized that although he might have been able to take Culps Hill, he couldn’t hold it with a single division after a counter attack from East Cemetery Hill. And surely that would be a general engagement. It’s possible that Ewell may have felt that it was practicable to take the hill, but did not see how he could do so without bringing on a general engagement. He only had 1 division on hand, it was getting dark, and he wasn’t going to receive any backup in any attack. He wanted support and none was available. Ewell did consider taking Culp’s Hill, which would have made the Union position on Cemetery Hill untenable. However, Jubal Early opposed the idea when it was reported that Union troops (probably Slocum’s XII Corps) were approaching on the York Pike, and he sent the brigades of John B. Gordon and Brig. Gen. William “Extra Billy” Smith to block that perceived threat. “Allegheny” Johnson’s division of Ewell’s Corps was within an hour of arriving on the battlefield and Early urged waiting for Johnson’s division to take the hill. After Johnson’s division arrived via the Chambersburg Pike, it maneuvered toward the east of town in preparation to take the hill, but a small reconnaissance party sent in advance encountered a picket line of the 7th Indiana Infantry, which opened fire and captured a Confederate officer and soldier. The remainder of the Confederates fled and attempts to seize Culp’s Hill on July 1 came to an end.

Ewell’s cautious approach and the lack of explicit orders from Lee contributed to his decision not to attack at that time. Lee’s order has been criticized because it left too much discretion to Ewell. Numerous historians and proponents of the Lost Cause movement (most prominently Jubal Early, despite his own reluctance to support an attack at the time) have speculated how the more aggressive Stonewall Jackson would have acted on this order if he had lived to command this wing of Lee’s army, and how differently the second day of battle would have proceeded with Confederate artillery on Cemetery Hill, commanding the length of Cemetery Ridge and the Federal lines of communications on the Baltimore Pike.

Another conundrum is whether or not Lee and Ewell were talking about the same hill. Lee was on Seminary Ridge and may have been looking at East Cemetery Hill while Ewell was at the base of Culp’s Hill. Yes, they are connected. But they are not the same hill. Did Lee & Ewell have a map that showed this? Lee spent the next two days trying to capture Cemetery Hill and it would make intuitive sense if this was the moment he recognized that it was the key to the Union position.

Military authorities and historians who have looked into the matter have pretty routinely concluded that Culp’s Hill would not have been easy to capture on July 1st. Ewell has been blamed for not aggressively pursuing the Union line on Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill, which left the Union on high ground. There is some controversy over whether Lee had been strong enough in his message to Ewell to take the ground. Some historians say that it’s 20/20 hindsight that Ewell could have easily pushed the Union line from the high ground; others say he was too timid. Stephen W. Sears has suggested that Gen. Meade would have invoked his original plan for a defensive line on Pipe Creek and withdrawn the Army of the Potomac, although that movement would have been a dangerous operation under pressure from Lee.

Lore & Legend

Although the story is a central part of Gettysburg lore, appearing in many books about the Civil War, it may not be accurate. And, it is also greatly negative against Ewell, and perhaps purposely so. The story may have been concocted by Lee’s apologists in a postwar attempt to shift the blame for losing the battle from their hero onto Ewell. In truth, Lee sent no definitive orders directing Ewell to pursue the enemy when the Union lines broke in front of the town, and Ewell was not benumbed by indecision when he defeated them in the town and on Barlow’s Knoll.

It was not until after the war, and Lee’s death, that Lost Cause supporters sought to explain how the infallible general wasdefeated at Gettysburg. Confederate veterans like John B. Gordon, Isaac Trimble and Randolph H. McKim insinuated in their postwar writings that it was Ewell’s timidity that had cost Lee the victory. Postwar proponents of the Lost Cause movement, particularly Jubal Early, criticized Ewell (and Longstreet in a separate issue) bitterly to deflect any blame for losing the battle on Lee. Part of their argument was that the U.S. soldiers were demoralized by their defeat earlier in the day. McKim’s 1915 article in The Southern Historical Society Papers stated. “Here then we find still another of General Lee’s lieutenants, the gallant and usually energetic Ewell, failing at a critical moment to recognize what ought to be done,” he wrote. “Had the advance on Cemetery Hill been pushed forward promptly that afternoon we now know beyond any possible question that the hill was feebly occupied, and could have been easily taken, and Meade would have been forced to retreat.”

Walter H. Taylor, Lee’s former aide, sided with the anti-Ewell faction in his memoir “Four Years With General Lee.” Taylor wrote that Ewell voiced no objection to the order he brought from Lee to take the high ground “if possible,” and that he returned to Lee under the impression Ewell would attack.

But there is another side to the story. Maj. Campbell Brown, Ewell’s stepson and aide, observed that the “discovery that this lost us the battle is one of those frequently-recurring but tardy strokes of military genius of which one hears long after the minute circumstances that rendered them at the time impracticable, are forgotten.” And while Taylor’s story became an important part of the controversy, Brown was adamant that he never brought such orders. In an 1885 letter to Gen. Henry Jackson Hunt, the former chief of artillery for the Army of the Potomac, Brown wrote, “I say broadly that Col. Taylor’s account of this battle is utterly worthless — that he carried no such order to Gen. Ewell … I do not impugn his veracity but his memory has been trusted and has deceived him.”

From there, the debate surrounding this order became extremely complicated and very personal after the war. The people who were actually there never agreed in their lifetimes what happened at that critical moment of history. What we read on Facebook and in history books hardly scratches the surface of this complex controversy. The next question raises just one example.

Major General Isaac Trimble, who was attached on special duty to Ewell’s command during the battle, was among those who tried to dismiss Lee’s warning. Writing for the Southern Historical Society (SHS) years after both Lee and Ewell had died, and quoted in DS Freeman page 569-570, Trimble recalled his attempt to persuade Ewell to attack:

“The battle was over and we had won it handsomely. General Ewell moved about uneasily, a good deal excited, and seemed to me to be undecided what to do next. I approached him and said: “Well, General, we have had a grand success; are you not going to follow it up and push our advantage?”

He replied that General Lee had instructed him not to bring on a general engagement without orders, and that he would wait for them.

I said, “That hardly applies to the present state of things, as we have fought a hard battle already, and should secure the advantage gained”. He made no rejoinder, but was far from composure. I was deeply impressed with the conviction that it was a critical moment for us and made a remark to that effect.

As no movement seemed immediate, I rode off to our left, north of the town, to reconnoitre, and noticed conspicuously the wooded hill northeast of Gettysburg (Culp’s), and a half mile distant, and of an elevation to command the country for miles each way, and overlooking Cemetery Hill above the town. Returning to see General Ewell, who was still under much embarrassment, I said, “General, There,” pointing to Culp’s Hill, “is an eminence of commanding position, and not now occupied, as it ought to be by us or the enemy soon. I advise you to send a brigade and hold it if we are to remain here.” He said: “Are you sure it commands the town?” [I replied,] “Certainly it does, as you can see, and it ought to be held by us at once.” General Ewell made some impatient reply, and the conversation dropped.”

— Isaac R. Trimble, “The Battle and Campaign of Gettysburg.” Southern Historical Society Papers 26 (1898).

Observers at the scene later reported that the “impatient reply” was, “When I need advice from a junior officer I generally ask for it.” They also stated that Trimble threw down his sword in disgust and stormed off.

Trimble was certainly upset that he was without a command on July 1. He would lose a leg and be captured 2 days later as he led a division in Pickett’s Charge, never to return to command. So, he certainly had plenty of scores to settle in 1898, 35 years later.

Conclusion

The if practicable order might be the most complex controversyin the entire Civil War genre. There seems to be no end to it, and no final answer. Did this famous episode really happen as it is stated? No one really knows. It’s common to suggest that Jackson would have attacked; but maybe that would not have been practical and not in keeping with Lee’s intent. Even 160 years later, it is unclear how Lee’s discretionary orders ought to have been responded to under the circumstances.

Counterintuitively, Ewell might well have made the right response to the order. Modern historical analysts suggest that taking Culp’s Hill at 5 pm would not have been easy, holding it against a counterattack very difficult, and that despite Gordon’s observations in his memoirs, that his brigades were in fact not ready to resume what would have been a very difficult assault.

Ewell himself never wrote or spoke about the matter in the 7 years he survived after the war.

References:

Leave a Reply