Introduction

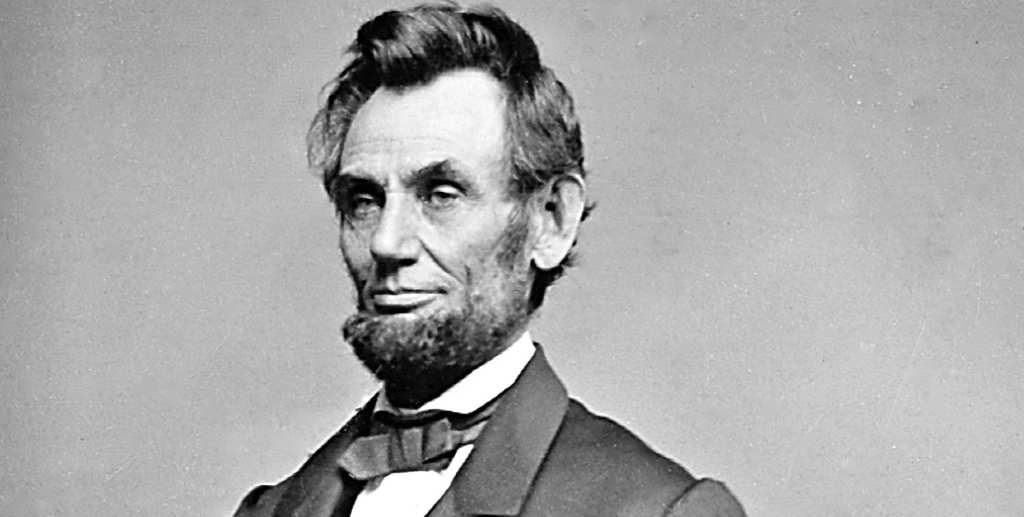

The suspension of Habeas Corpus by President Lincoln at the start of the Civil War is often misunderstood and presented to modern readers with a lack of historical context. In some discussions, it is averred that Lincoln violated the Constitution and was therefore a tyrant: “Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus shows he didn’t care about the Constitution”. Indeed, the official Maryland state song until 2 years ago said exactly that.

The purpose of this article is to provide the history behind the action and summarize its legal implications. It offers historical context and legal implications regarding Abraham Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War. The suspension was a response to the Baltimore Riot and the need to defend Washington, D.C. Lincoln’s decision to suspend habeas corpus was challenged in the case of Ex parte Merryman, where Chief Justice Roger Taney ruled that only Congress had the power to suspend habeas corpus. However, Lincoln disregarded Taney’s order and continued with additional suspensions. Eventually, Congress formally suspended habeas corpus with the passage of the Habeas Corpus Act in 1863. While the legality of Lincoln’s actions remains debated, it is generally believed that Lincoln had the legal right to declare martial law as commander in chief during a time of rebellion and war.

The Baltimore Riot

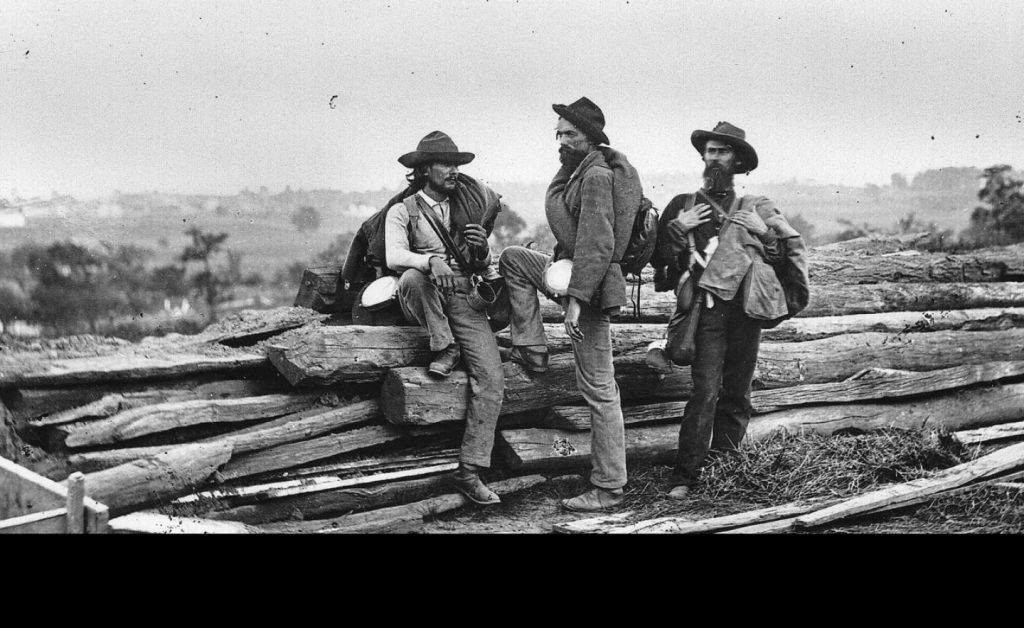

In April 1861, secession had been declared by 7 states. The possibility of war was now a real question, especially following the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12-14. Lincoln called up militia units into service and wanted them posted in Washington DC for its defense. The only direct rail route from the northern states was through Baltimore, a city in a border state with significant southern sympathies.

The Baltimore Riot, also called the Pratt Street Riots, ensued on Friday, April 19, 1861. This armed conflict occurred between Copperheads and other Southern sympathizers against members of Massachusetts and Pennsylvania state militia regiments who were en route to Washington. Baltimore had two trains with different gauges separated by the waterfront, requiring passengers who wanted to get to Washington to change trains. The fighting began at the President Street Railroad Station where the militia debarked its incoming train, spread throughout President Street, and finally to Howard Street, ending at the Camden Street Station, where the train to DC was located Four soldiers were killed, 36 wounded, and 12 civilians were also killed. It is often said that this was the first actual bloodshed in the war.

Afterwards, the Governor of Maryland, Governor Thomas Hicks, asked President Lincoln not to send troops though Baltimore on their way to Washington, It remains uncertain if his motivation in asking Lincoln to find an alternate transportation route was to quell the violence or to block the passage of troops, cutting off Washington. Hicks was a Know-Nothing former Whig who had barely defeated the Democratic candidate in a highly fraudulent 1859 election. That election involved fake voters, intimidation of voters, and violence. In his inaugural address, Hicks’ main theme was criticizing the influx of immigrants into America. He opposed abolition, favored enforcement of fugitive slave laws, but opposed secession, albeit weakly and late.

Ex Parte Merryman

Lincoln refused to find an alternative route, citing the complexity involved but also demanding that Maryland remain loyal. Consequently, Hicks along with other Maryland politicians approved militia captain John Merryman to burn the railroad bridges leading to Baltimore. Later, Hicks denied ordering Merryman to do so, but his denials were unconvincing. Merryman was a prominent planter from Baltimore County, Maryland and a public official.

John Merryman

On April 27, 1861, Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus between Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia to give military authorities the necessary power to silence dissenters and rebels. By this act, military personnel could arrest anyone who was thought could threaten military operations. The danger to the capital was genuine and grave; thus, Lincoln delegated limited authority to the Army to suspend habeas corpus in Maryland. He told General Winfield Scott that if there was any resistance on the “military line” from Annapolis to Washington, Scott or “the officer in command at the point” was authorized to suspend habeas corpus if necessary. On May 13, martial law was declared.

This sequence of events led to a fascinating constitutional and political wrangle when Merryman was arrested one month later. Merryman was arrested on May 25 by order of Brigadier General William High Keim of the United States Volunteers for his role in destroying the bridges. The reason for his arrest was that he was “an active secessionist sympathizer.” He was also charged with communication with the Confederates and with treason. Since his crime involved military actions and he was arrested and held by military officials under martial law, a military court was to hear his case.

Merryman asked to be removed from prison and given a trial in a civilian court. Instead, he was imprisoned in Fort McHenry in Baltimore harbor. There, he was inaccessible to the civilian courts and legal authorities. Moreover, General Keim would not make Merryman available to meet with his attorneys.

Judge William Fell Giles of the US District Court for Maryland issued a writ of habeas corpus, but the order was ignored. Two weeks later, Merryman’s lawyers went to Washington demanding that Merryman be produced to meet with them (that is what habeas corpus means), and Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney promptly issued the writ on Merryman’s behalf. The writ merely asked that he be produced in court, not released. Merryman was held in defiance of a writ of habeas corpus, which led to the case of Ex parte Merryman.

When the general in charge, General Cadwalader, did not produce him, he was violating the writ. He had been ordered not to do so by Army HQ under Lincoln’s orders. (There were other complicating factors, such as whether a US Marshall had been admitted to the fort to deliver the writ; legally, if it’s not received, it’s not operative.)

Justice Roger Taney

Justice Taney’s Ruling

The case came before Justice Taney, sitting as a circuit court judge, as the Supreme Court was not in session. Taney issued the writ in Maryland, not DC, which has raised many questions during the past 160+ years whether he was acting as a circuit court judge or a SCOTUS justice. Taney ruled in this case the authority to suspend habeas corpus lay exclusively with Congress. He stated that the President can neither suspend habeas corpus nor authorize a military officer to do it, and that military officers cannot arrest a person not subject to the rules and articles of war, except as ordered by the courts. Taney cited historical precedent and the placement of the Suspension Clause in Article I, which discusses the Legislature’s Role in government.

Taney’s opinion was focused on two points. First, only Congress, and not the President, had the power to suspend habeas corpus. Taney ruled that the power to suspend habeas corpus was not given to the President, and could not be inferred from the President’s listed duties in the Constitution. Instead, the potential conditions for its suspension were listed in Article I, which deals with the powers of Congress. Taney quoted past Supreme Court Justices who had written that the power to suspend habeas corpus belonged to Congress. Secondly, even if the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus had been suspended by an act of Congress, only someone in the military could be held and tried by a military commission. On this point, trying Merryman in a military court had no legal basis.

Taney believed that Lincoln was violating the Constitution’s provisions, guarantees, and checks and balances. He wrote,

“[I]f the authority which the Constitution has confided to the judiciary department and judicial officers [to judge the legality of imprisonments], may thus, upon any pretext or under any circumstances, be usurped by the military power, at its discretion, the people of the United States are no longer living under a government of laws…”

Lincoln’s Response

President Lincoln disregarded Taney’s order and continued ordering suspensions of the writ in additional areas. He claimed that his oath to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution required him to take these actions. Speaking before Congress on July 4, 1861, Lincoln asked ironically, “Are all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces, lest that one be violated?” On Sept. 24, 1862, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus throughout the nation. Anyone rebelling against the US would be jailed, denied a jury trial, and tried in military court instead.

Congress did eventually adopt language recognizing Lincoln’s actions, and did suspend habeas corpus legally. In March of 1863, two years after Lincoln’s first suspension order, Congress formally suspended habeas corpus with the passage of the Habeas Corpus Act. Merryman was never tried, as Taney continued to delay hearing the case for years. Since capital punishment was the punishment for treason (burning bridges), it was probably just as well for Mr. Merryman. Many authorities believe that Taney’s rulings were made as he sat as chief magistrate of the First Circuit Court, not as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and thus his opinion had no bearing on the constitutionality of Lincoln’s action.

The Supreme Court ruled in the 1863 Prize Cases that Lincoln had been well within his powers as president to respond to acts of rebellion without the consent of congress in April since the legislative branch had been out of secession.

Implications

Practically, the dispute had no effect: Lincoln simply ignored and refused to honor the writ. The inability of the judiciary to enforce its decision meant that Lincoln’s suspension of the writ would go unchallenged and arrests would continue.

Habeas corpus is a legal term derived from the Latin: ‘that you have the body’. It is a legal means by which an unlawful detention or imprisonment can be objected to in court. A writ of habeas corpus is a court order that the custodian, usually a prison official, must bring the prisoner to court, to determine whether the detention is lawful. It is a precept of law that habeas corpus is a central tenet of a free society that prevents government from illegally arresting people without recourse.

The suspension of habeas corpus is authorized by Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution during times of rebellion or when public safety is in danger. The constitutional question raised in ex parte Merryman was whether it could be suspended by the President or had to be suspended by Congress.

The Taney decision has been criticized as being partisan against Lincoln. Lincoln’s argument was that Congress was out of session and it was an urgent matter of national security during a time of rebellion to arrest a man who committed treason. Most legal scholars think Lincoln had it right. In opposition, Justice Scalia supported the legal argument holding that Congress alone may suspend the writ in a dissenting opinion, joined by Justice John Paul Stevens, in the case of Hamdi v. Rumsfeld.

Current legal thinking is that Lincoln had the legal right to declare martial law by his position as commander in chief. Thus, although the legal question of Lincoln’s decision remains ambiguous, his act was defensible legally and constitutionally. Lincoln and the Union were in a time of insurrection and war. Congress was not in session. Congress approved his suspension when they were back in session.

Leave a Reply